Deep Learning: Natural Language Processing (Part 1)

Content

- Content

- A Comprehensive Learning Path to Understand and Master NLP in 2020

- Deep Feed Forward Network

- Gradient-Based Learning

- Short Summary of RNN, LSTM, GRU

- What is BPTT and it’s issues with sequence learning ?

- Vanishing Gradient in CNN and RNN:

- What is Exploding Gradient Problem??

- How does LSTM help prevent the vanishing (and exploding) gradient problem in a recurrent neural network?

- Why can RNNs with LSTM units also suffer from “exploding gradients”?

- Preventing Vanishing Gradients with LSTMs

- Gating in Deep learning

- Use of Sigmoid and Tanh

- Understand forward and backward with simple Perceptron

- Loss Functions in Deep learning

- Different loss function and their pros and cons?

- TODO: What is LSTM’s pros and cons?

- How does

word2vecwork? - What is Transfer Learning, BERT, Elmo, UmlFit ?

- What is model Perplexity?

- What is BLEU score?

- What is GLUE?

- Different optimizer Adam, Rmsprop and their pros and cons?

- Autoencoders

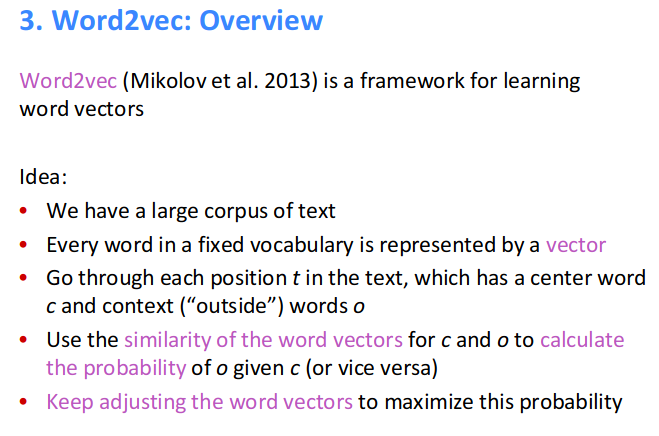

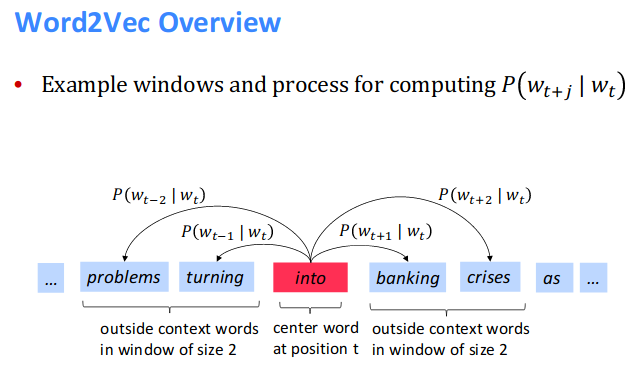

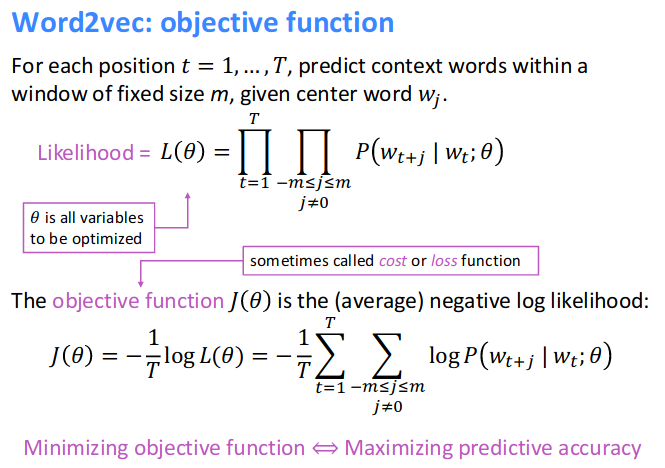

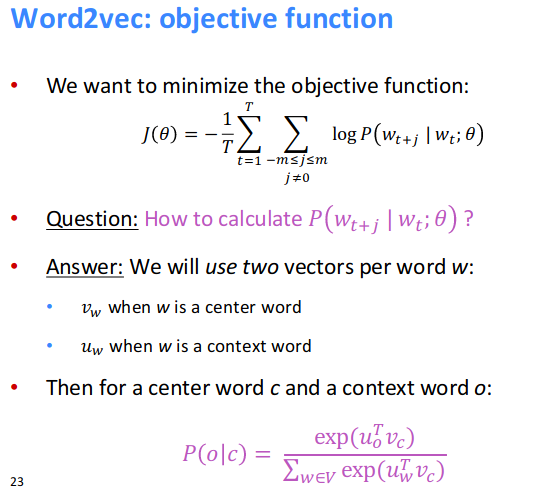

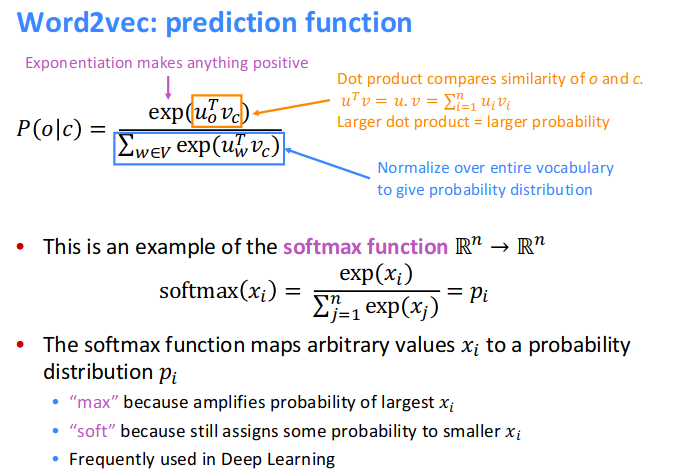

- Word2Vec

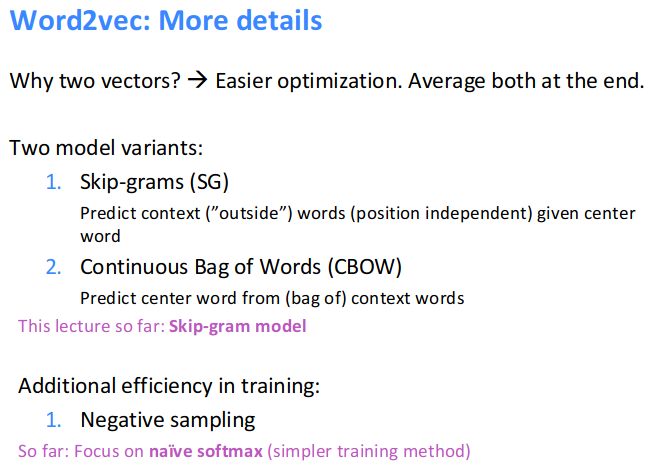

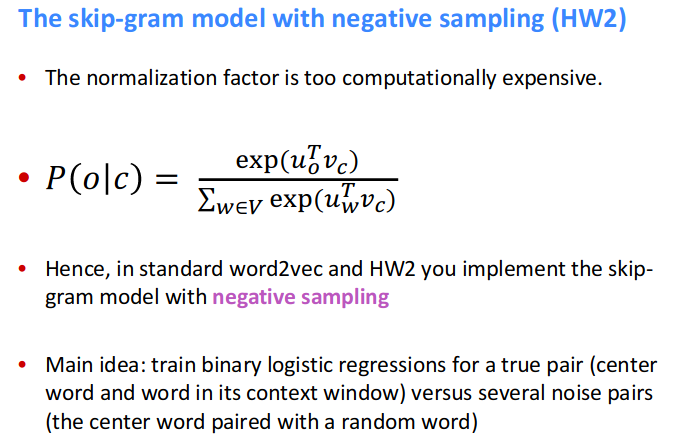

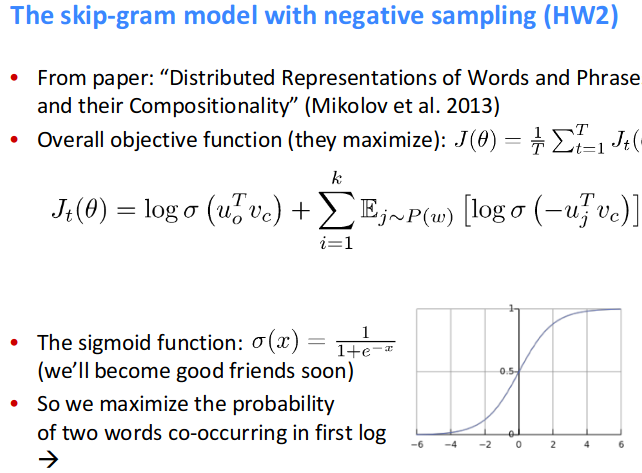

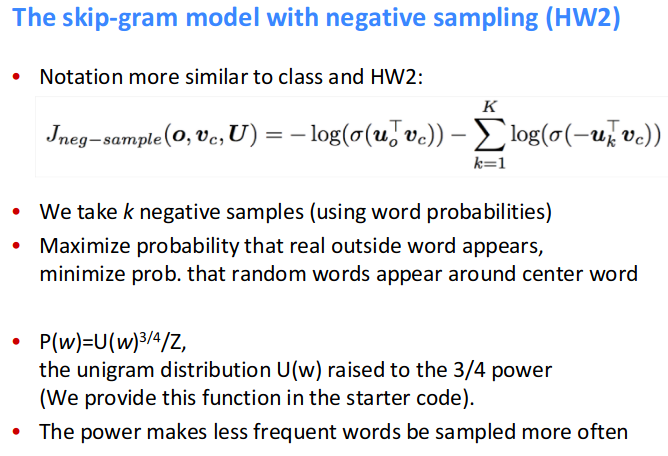

- Word2Vec - Skip Gram model with negative sampling

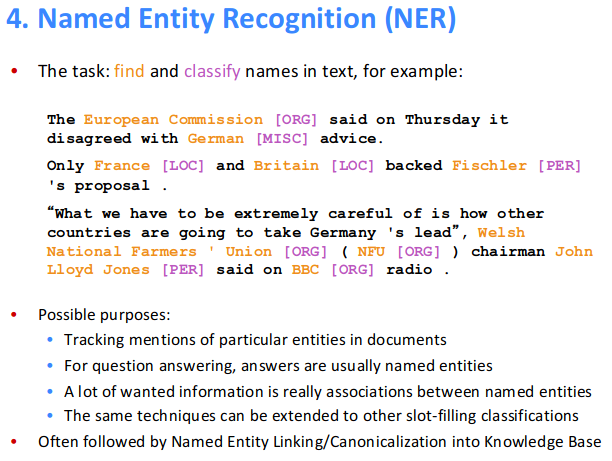

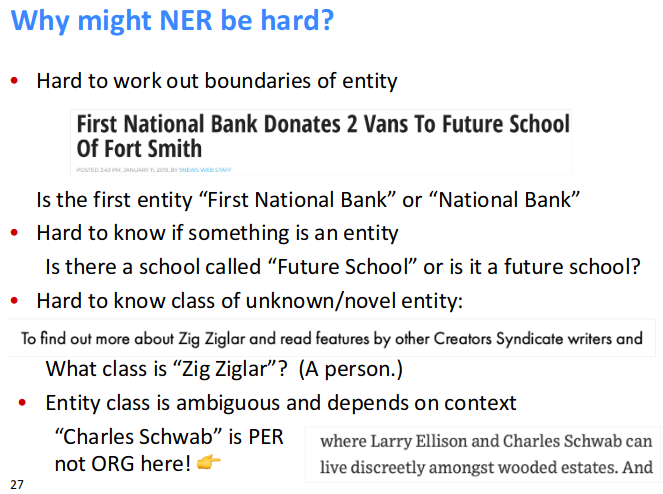

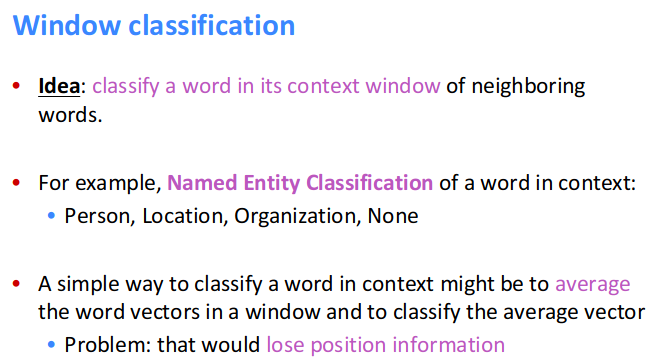

- Named Entity Recognition

- Word embedding - Implementation

- LSTM demystified

- Why the input/output gates are needed in LSTM?

- Vanishing Gradient Problem in general

- How does LSTM solve vanishing gradient problem?

- How can you cluster documents in unsupervised way?

- How do you find the similar documents related to some query sentence/search?

- Explain TF-IDF?

- What is word2vec? What is the cost function for skip-gram model(k-negative sampling)?

- How can I design a chatbot ?

- Exercise

Quick Refresher: Neural Network in NLP

A Comprehensive Learning Path to Understand and Master NLP in 2020

- Follow

this wonderful learning path.

this wonderful learning path.

Deep Feed Forward Network

- These models are called Feed Forward Network because the information flows from $x$, through the intermediate computations used to define $f$ and finally to the output $y$.

- When FFN are extended to include feedback loops, they are called recurrent neural network.

- The dimensionality of the hidden layer decides the width of the model.

- The strategy of deep learning is to learn $\phi$. In this approach, we have a model $y=f(x;\theta,w)=\phi(x;\theta)^Tx$. We now have $\theta$, that we use to learn $\phi$ from a broad class of functions and parameter $w$ that map from $\phi(x)$ to the desired output. This is an example of deep FNN and $\phi$ denotes the hidden layer.

- This approach gives up the convexity of the training problem but the benefits out-weight the harm.

- FFN has introduced the concept of hidden layer, and this requires us to choose the activation function to compute the the hidden layer values and brings non-linearity into the system.

Gradient-Based Learning

- The biggest difference between linear models and neural network is that the non-linearity of neural network causes the most interesting loss function to become non-convex.

- Neural network models are trained by using iterative, gradient based optimizers, that merely drive the cost function to a very low value.

- Where as linear equation solvers used to train linear regression models or the convex optimization algorithms, with global convergence guarantees used to train logistic regression or SVMs.

- SGD applied to non-convex loss function has no convergence guarantees, and is sensitive to the initial parameter values.

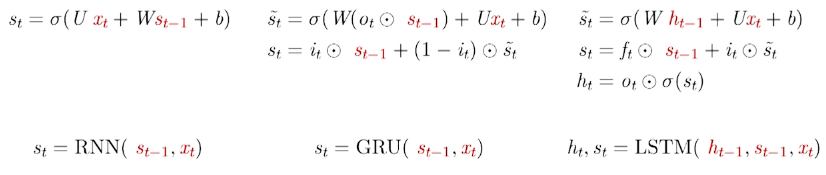

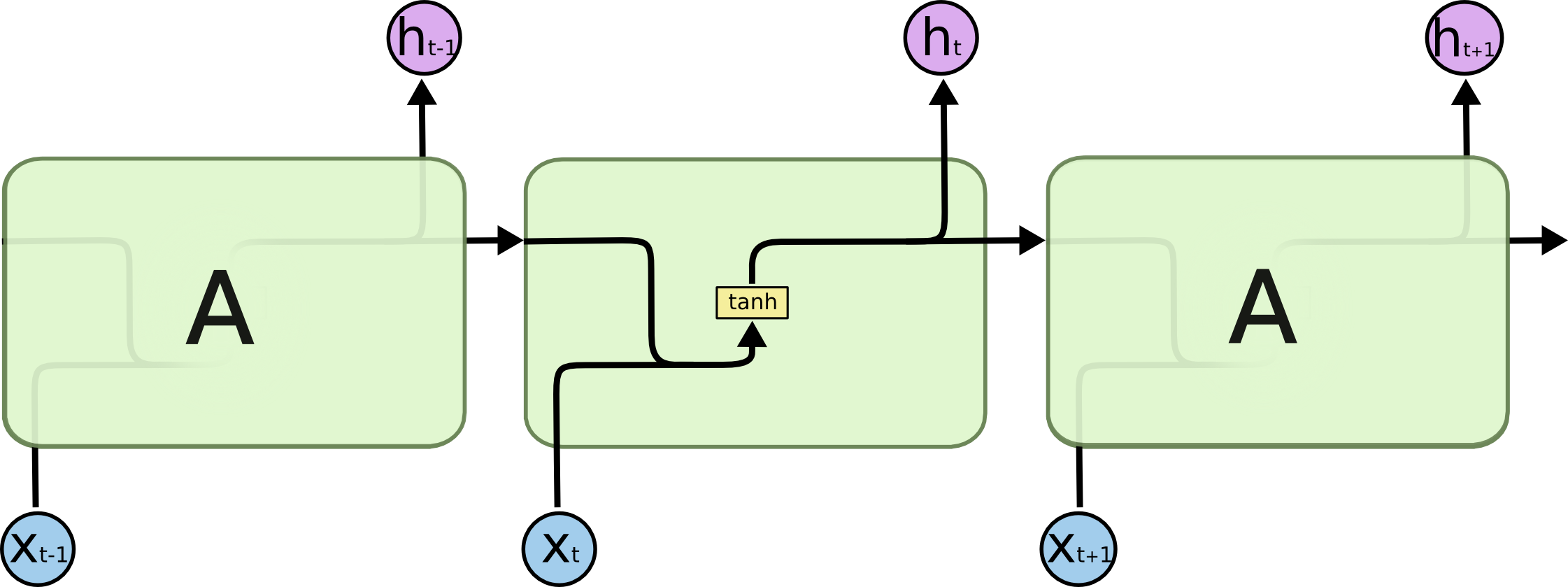

Short Summary of RNN, LSTM, GRU

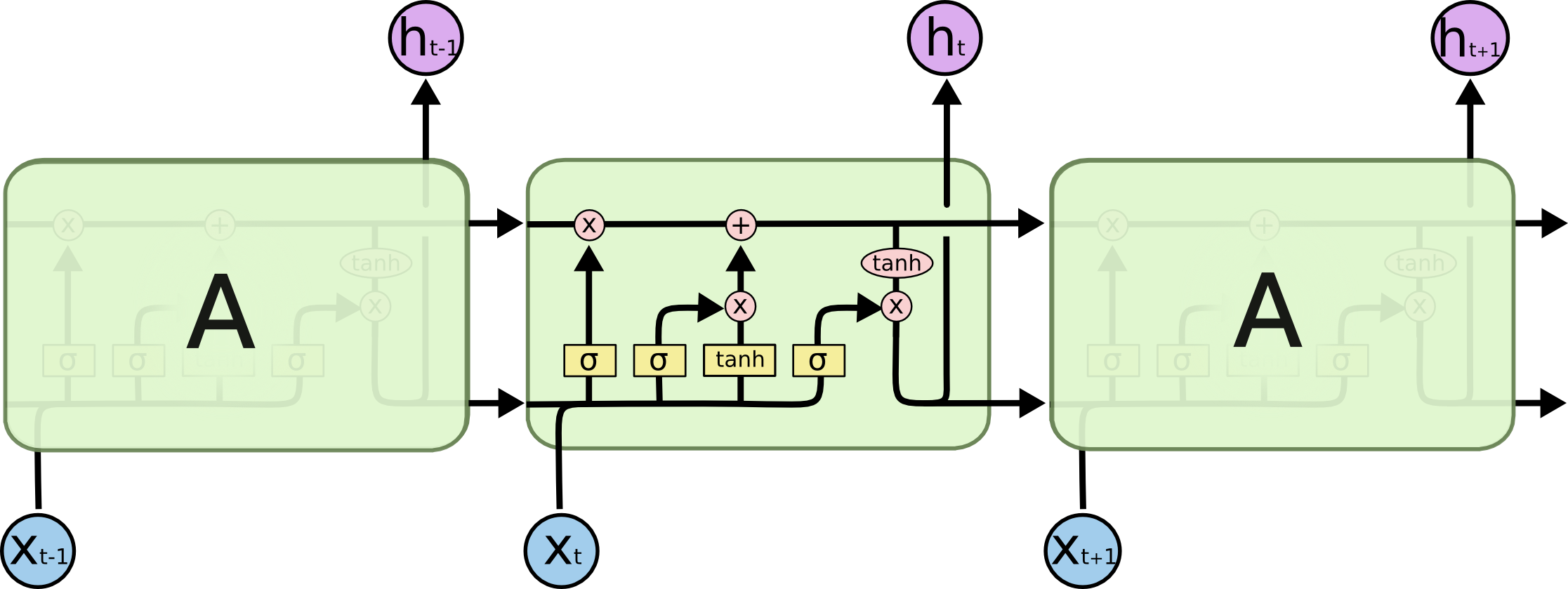

- RNN reads the document left to right and after every word updates the state. By the time it reaches the end of the word, the information obtained from the

first fewwords, are completely lost. So we need some mechanism to retain these information. - Now the most famous architecture is

LSTMto address the above issues of RNN. The general idea is to implement 3 primary operationsselective read,selective writeandselective forget. i.e forget some old information, create new information and update the current information. - All the variations of

LSTMimplemented these 3 operations with some tweak, like merging 2 operations into 1 and many more.

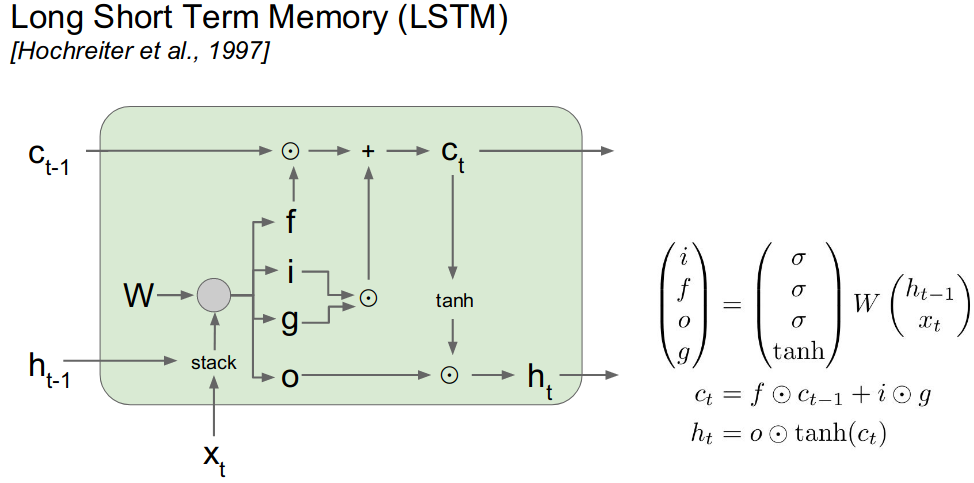

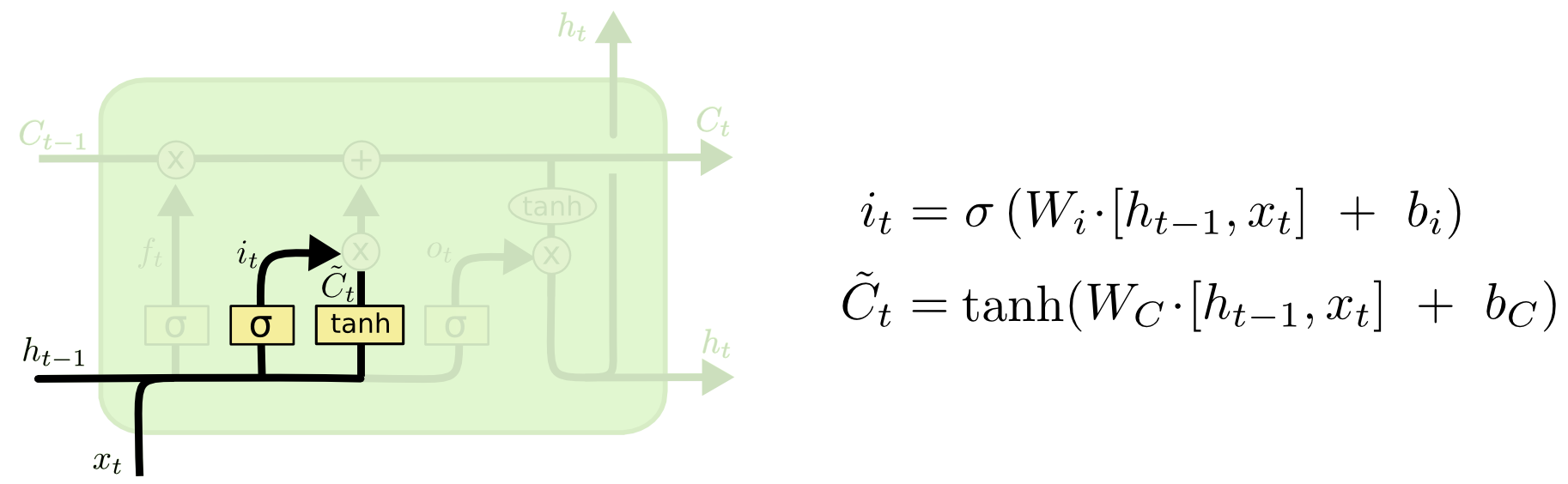

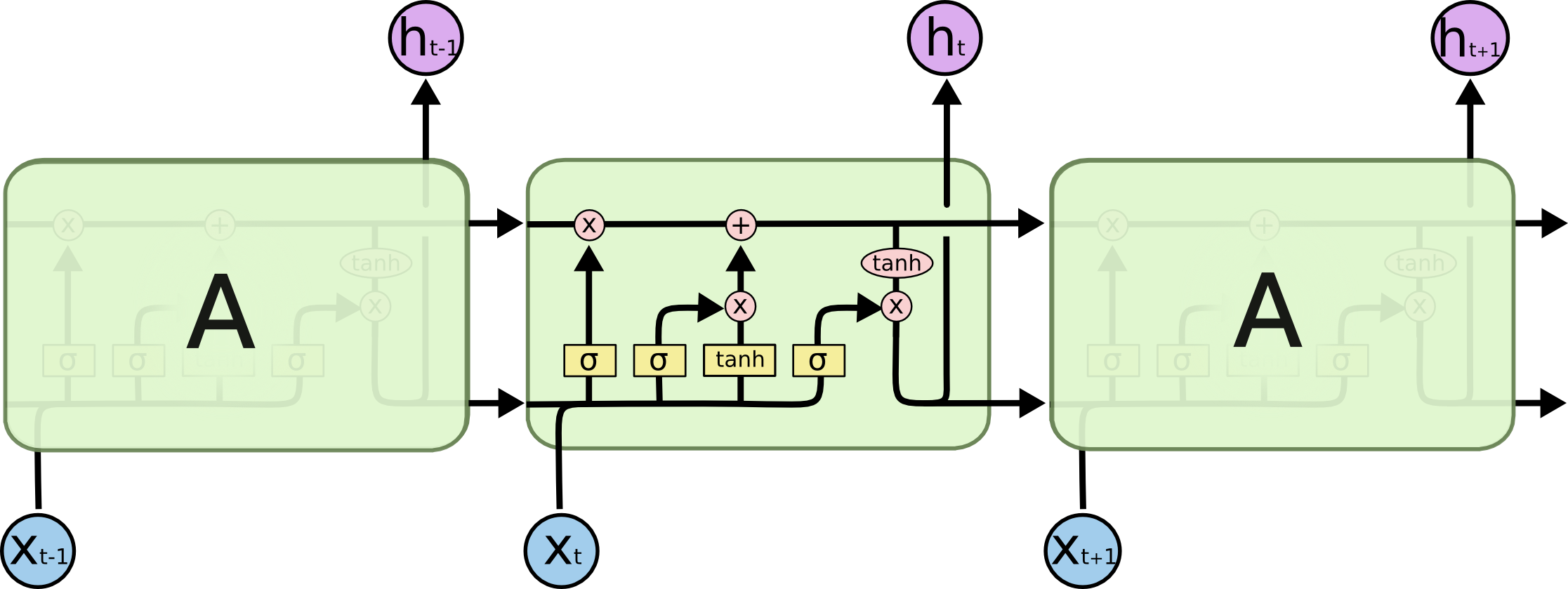

LSTM

- In the most popular version of LSTM, in each LSTM cell these 3 operations are implemented as 3

Gate-

selective forgetimplemented byforget gate$f_t$ -

selective readimplemented byinput gate$i_t$ -

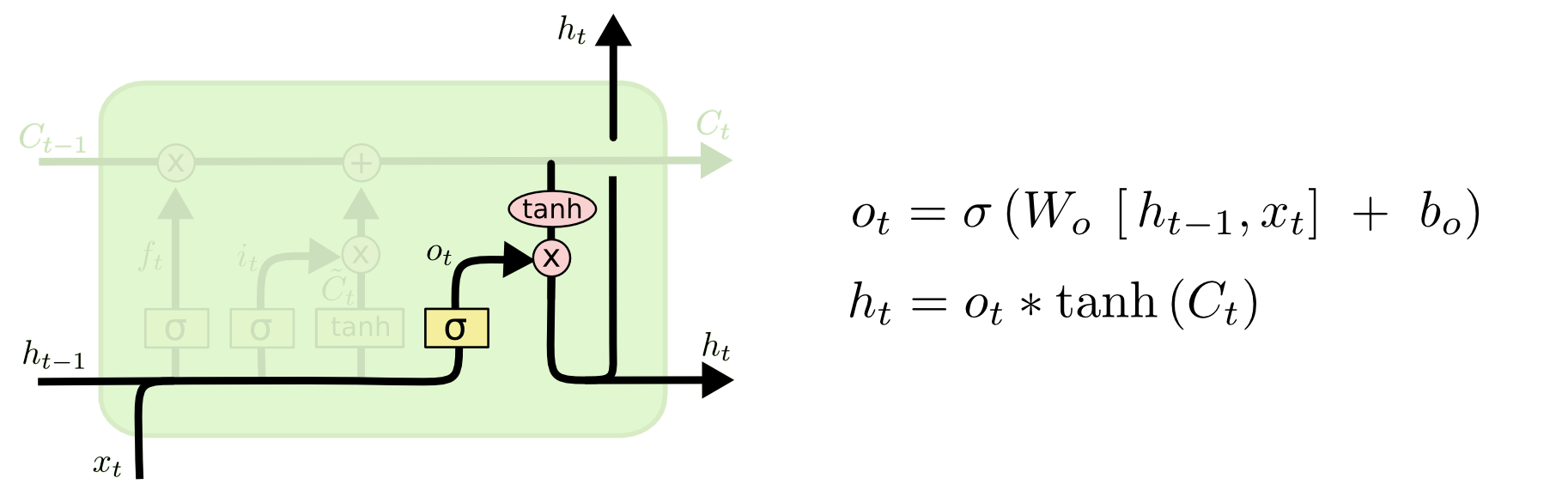

selective writeimplemented byoutput gate$o_t$

-

- Each LSTM cell also has 2 states

- $h_t$: output/hidden state (similar to hidden state of RNN)

- $C_t$: Cell state or

running statethat acts as a memory containing a fraction of information from all the previous timestamps $t$

Gates

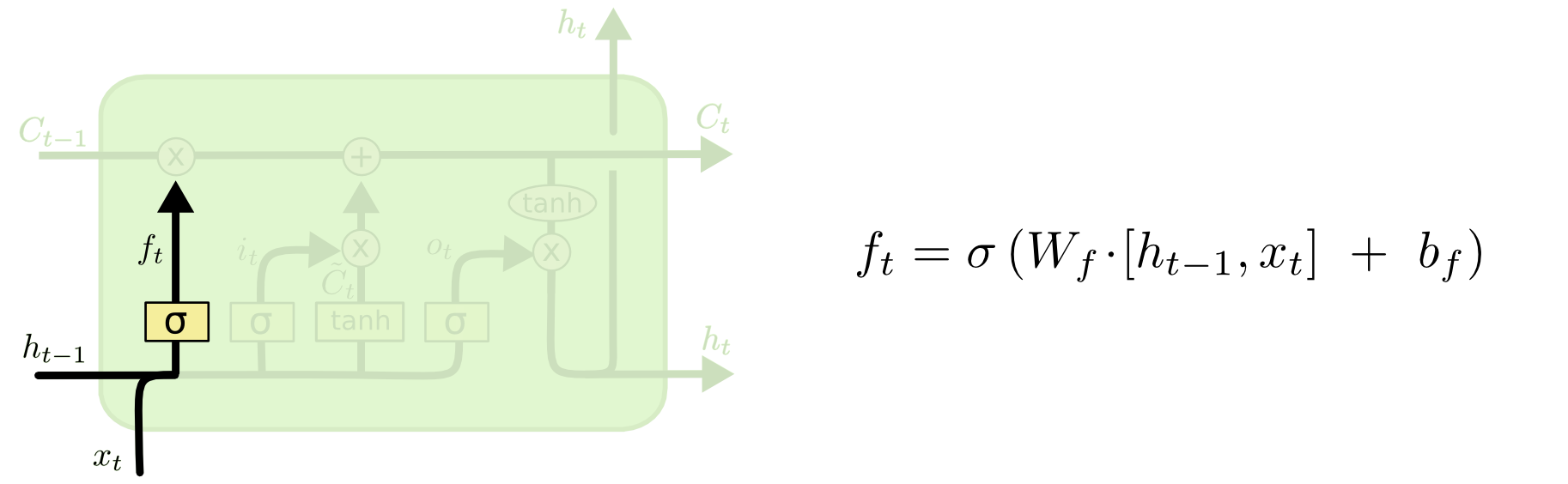

- Forget Gate: $f_t = \sigma (W_f h_{t-1} + U_f x_t + b_f)$

- Input / Read Gate: $i_t = \sigma (W_i h_{t-1} + U_i x_t + b_i)$

- Output / Write Gate: $o_t = \sigma (W_o h_{t-1} + U_o x_t + b_o)$

$f_t$, $i_t$, $o_t$ decides the fraction of {$\in [0,1]$} forget, read and write respectively.

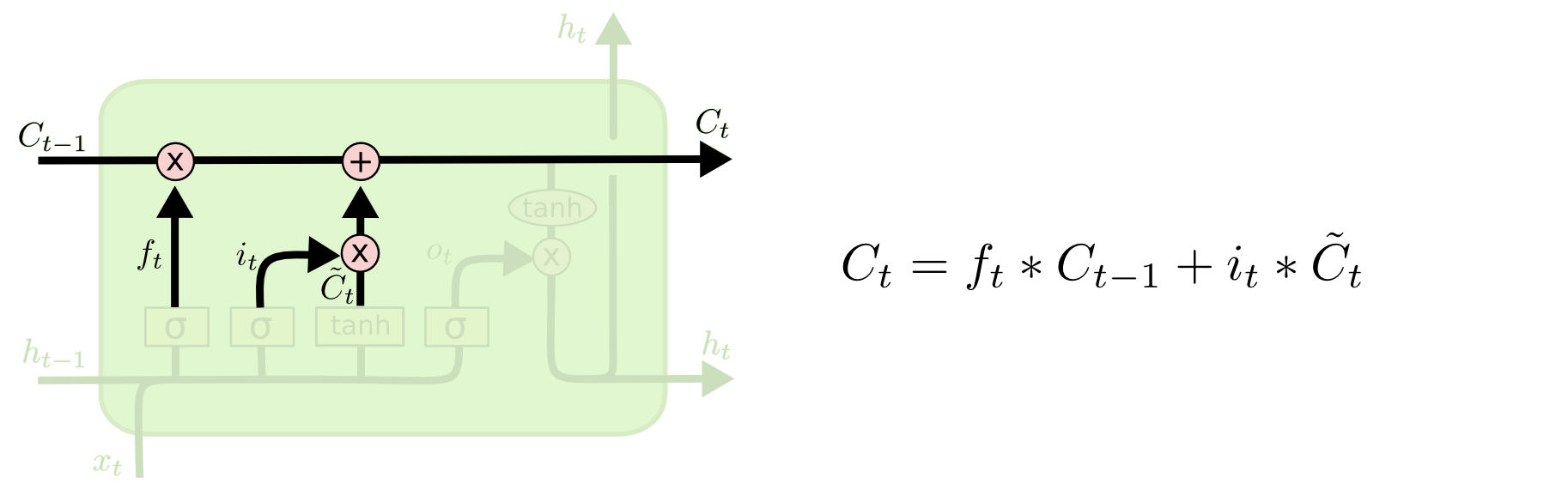

States

- New Content: $\tilde{C_t} = \sigma(WH_{t-1} + Ux_t + b)$

- Cell / Running State: Obtained from new content after applying selective forget and read: $C_t = f_t \odot C_{t-1} + i_t \odot \tilde{C_t}$

- Output / Hidden state: $h_t = o_t \odot \sigma(C_t)$

Combining all together:

Where $\tilde{C_t}$ is the new input or content which will be used to update the current cell state $C_t$ by forgetting a fraction $f_t$ of old cell state $C_{t-1}$ (selective forget) + adding fraction $i_t$ of new cell input $\tilde{C_t}$ (selective read). Finally $h_t$ is obtained by doing a selective write with the fraction $o_t$ and cell state $C_t$. Note $\odot$ is called the pointwise product or the hadamard product.

image source, cs231n, lecture 10 page 96

image source, cs231n, lecture 10 page 96

- For reference check the blog of Chris Olah and the lecture of Prof. Mitesh K. However, in Chris Olah’s blog, he has concatenated $h_{t-1}$ and $x_t$, which leads to learning of fewer parameter.

- In Prof.Mitesh K’s lecture, he has used notation $s_t$ for cell state.

Quick Summary

Different Variation of LSTM

What we have described so far is a pretty normal LSTM. But not all LSTMs are the same as the above. In fact, it seems like almost every paper involving LSTMs uses a slightly different version. The differences are minor, but it’s worth mentioning some of them.

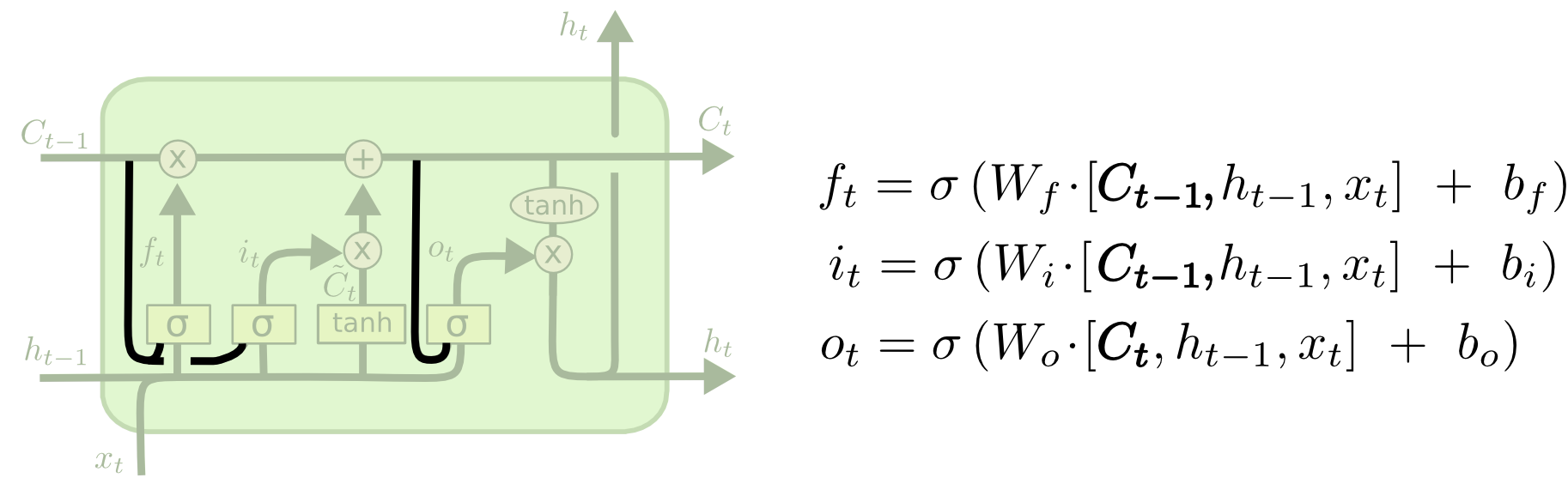

Peep-hole LSTM

One popular LSTM variant, introduced by Gers & Schmidhuber (2000), is adding peephole connections. This means that we let the gate layers look at the cell state.

The above diagram adds peepholes to all the gates, but many papers will give some peepholes and not others.

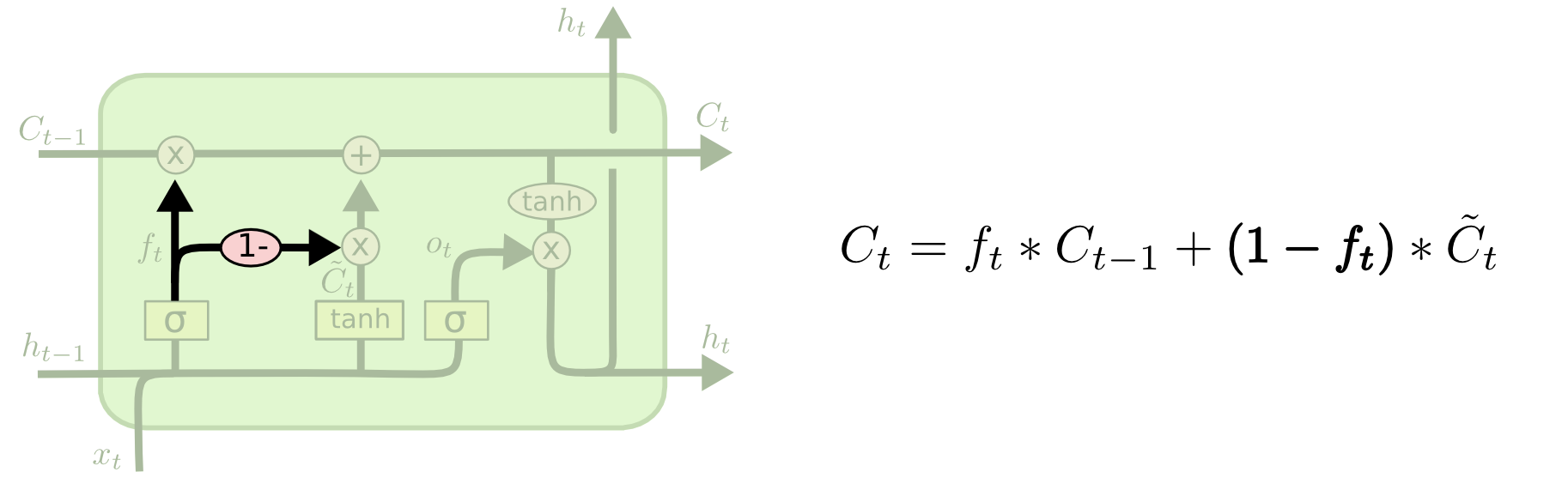

Coupled forget and input gates

Instead of separately deciding what to forget and what we should add new information to, we make those decisions together. We only forget when we’re going to input something in its place. We only input new values to the state when we forget something older.

This is the backbone of GRU.

GRU

A slightly more dramatic variation on the LSTM is the Gated Recurrent Unit, or GRU, introduced by Cho, et al. (2014).

It combines the forget and input gates into a single “update gate.” It also merges the cell state and hidden state, and makes some other changes. The resulting model is simpler than standard LSTM models, and has been growing increasingly popular.

Which of these variants is best? Do the differences matter? Greff, et al. (2015) do a nice comparison of popular variants, finding that they’re all about the same. Jozefowicz, et al. (2015) tested more than ten thousand RNN architectures, finding some that worked better than LSTMs on certain tasks.

![]() Reference:

Reference:

- IMP, Lecture 10, Standford cs231 page-96

-

Chrish Olah LSTM

-

Illustrated Guide to LSTM’s and GRU’s

- Lecture 15 by Prof. Mitesh K

- Edward Chen

What is BPTT and it’s issues with sequence learning ?

Total Loss: In sequence learning (RNN, LSTM, GRU etc.) the total loss is simply the sum of the loss over all the time steps.

- Take a pause and think that for non sequence learning, there is no concept of each time step and they have only single loss function.

- In normal backpropagation, you need to get the gradient w.r.t weight and bias using chain rule and done.

- Whereas, in sequence learning due to the presence of time step, you need to get the

loss gradientfor each time step and then aggregate them.

So total loss for sequence learning is

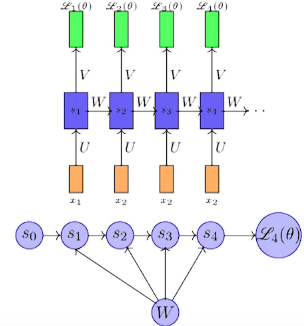

In the above image is a simple vanilla RNN, where $t$ is from $1$ to $4$. For back propagation we need to compute the gradient w.r.t $W$, $U$, $V$.

Now taking derivative w.r.t $V$ is straight forward.

Problem arrives now while taking derivative w.r.t $W$.

However, while applying chain rule $L_4(\theta)$ is dependent on $s_4$, $s_4$ is dependent on $W$ and $s_3$, $s_3$ is dependent on $s_2$ and so on. So while taking derivative of $s_i$ w.r.t $W$, we can’t take $s_{i-1}$ as constant. That’s the problem in such ordered network

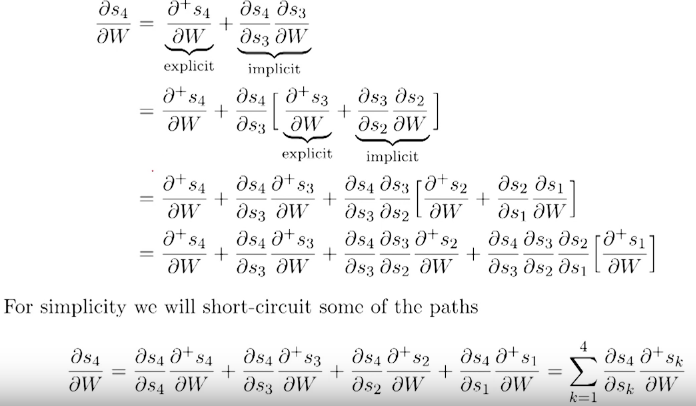

Therefore, in such network the total derivative $\frac{\delta s_4}{\delta W}$ has 2 parts.

- Explicit: Treating all other input as constant

- Implicit: Summing over all indirect paths from $s_4$ to $W$.

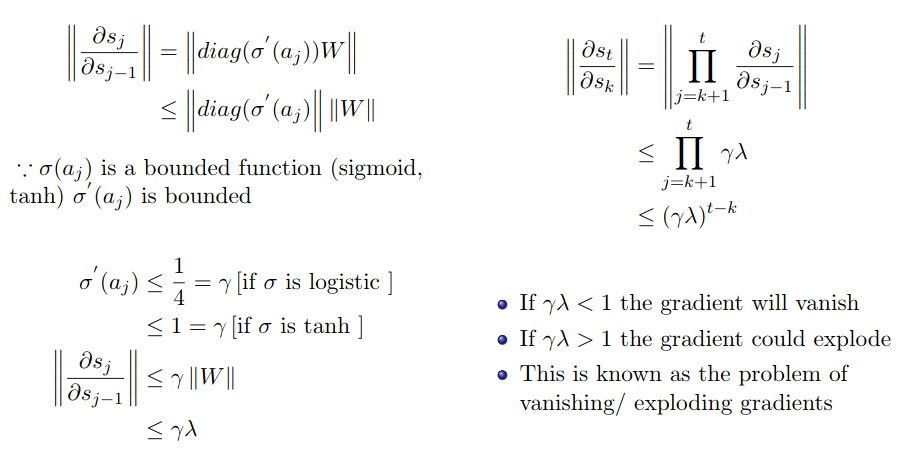

Vanishing and Exploding gradient problem in BPTT

So we got

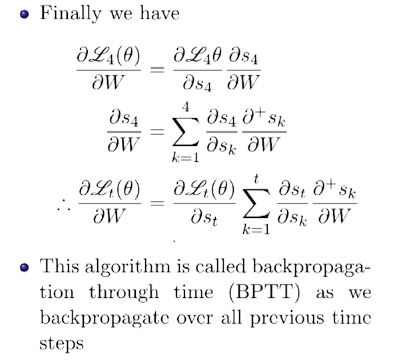

However we will now focus on $\frac{\delta s_t}{\delta s_k}$ which is causing a problem in training RNN using BPTT.

Therefore the earlier equation becomes

Now we are interested in the magnitude of $\frac{\delta s_{j+1}}{\delta s_{j}}$.

- If $\frac{\delta s_{j+1}}{\delta s_{j}}$ is small, i.e $\lt 1$, then on repeated multiplication, it will vanish, $\Rightarrow$ $\frac{\delta s_{t}}{\delta s_{k}}$ will vanish $\Rightarrow$ $\frac{\delta L_t(\theta)}{\delta W}$ will vanish.

- If $\frac{\delta s_{j+1}}{\delta s_{j}}$ is large, i.e $\gt 1$, then on repeated multiplication, it will explode, $\Rightarrow$ $\frac{\delta s_{t}}{\delta s_{k}}$ will explode $\Rightarrow$ $\frac{\delta L_t(\theta)}{\delta W}$ will explode.

![]() Note: Here $s$ is

Note: Here $s$ is cell state, and $j$ is the time step, thus we can write in more meaningful way as $\frac{\partial C_{t+1}}{\partial C_{t}}$)

From Lecture 14 by Prof.Mitesh K,

Resource:

- Lecture 14 by Prof.Mitesh K

- Youtube lecture by Prof. Mitesh K

- Blog by Danny Britz from WINDML

- Softmax Derivative

- RNN Derivative

Vanishing Gradient in CNN and RNN:

![]() Vanishing gradient over different time-steps in same layer: When talking about RNN, the vanishing gradient problem refers to the

Vanishing gradient over different time-steps in same layer: When talking about RNN, the vanishing gradient problem refers to the change of gradient in one RNN layer over different time steps (because the repeated use of the recurrent weight matrix).

![]() Decaying gradients over different layers: On the contrary, when talking about CNN, it is about the

Decaying gradients over different layers: On the contrary, when talking about CNN, it is about the gradient change over different layers, and it is generally referred to as “gradient decaying over layers”. Just for your information, the recent IndRNN model addresses the vanishing and exploding gradient problems. It is much more robust than the traditional RNN.

- If you just keep on adding convolution layers to a CNN , after a point you will start facing vanishing gradient. You can experiment this using the vgg architecture.

-

Solution: To avoid this problem and build deeper networks , most of the modern architectures uses

Solution: To avoid this problem and build deeper networks , most of the modern architectures uses skip connectionslike in Resnet , Inception. These modern architectures go deeper to more than 150 layers.

-

- RNNs unfolded are deep in common application scenarios, thus prone to severe vanishing gradient problems. For example, when used in language modeling,

RNN depth can go as long as the longest sentence in the training corpus. If the model is character-based, then the depth is even larger. CNNs in typical application scenarios areshallower, but still suffer from the same problem with gradients. - Images typically have

hierarchy of scales, so parts of the image which are far away from each other typically interact only athigher order layers of the network.- For RNN parts which are far far away from each other can huge influence. e.g. If you smoke when you are young, you may have cancer 40 years later. RNN should be able to make predictions based on very long term correlations.

TL;DR: Deeper networks are more prone to Vanishing Gradient problem. Now RNNs are (after unfolding) very deep. So they suffer more from Vanishing Gradient problem. Here the Vanishing Gradient problem occurs at the gradient change at the same RNN layer. But CNN by default is shallow network. Here if you stack multiple CNN layer, then vanishing gradient occurs at decaying of gradient at different layer.

Resource:

What is Exploding Gradient Problem??

TL;DR: Exploding gradients are a problem where large error gradients accumulate and result in very large updates to neural network model weights during training. This has the effect of your model being unstable and unable to learn from your training data.

What Are Exploding Gradients?

An error gradient is the direction and magnitude calculated during the training of a neural network that is used to update the network weights in the right direction and by the right amount.

In deep networks or recurrent neural networks, error gradients can accumulate during an update and result in very large gradients. These in turn result in large updates to the network weights, and in turn, an unstable network. At an extreme, the values of weights can become so large as to overflow and result in NaN values.

The explosion occurs through exponential growth by repeatedly multiplying gradients through the network layers that have values larger than $1.0$.

How do You Know if You Have Exploding Gradients?

There are some subtle signs that you may be suffering from exploding gradients during the training of your network, such as:

- The model is unable to get traction on your training data (e.g. poor loss).

- The model is unstable, resulting in large changes in loss from update to update.

- The model loss goes to NaN during training.

There are some less subtle signs that you can use to confirm that you have exploding gradients.

- The model weights quickly become very large during training.

- The model weights go to NaN values during training.

- The error gradient values are consistently above 1.0 for each node and layer during training.

how to fix Exploding or Vanishing Gradient in sequence model?

- Truncated BPTT, i.e, you will not look back more than $k$ time-steps where $k \lt t$

- Gradient Clipping

Resource:

How to Fix Exploding Gradients?

![]() Re-Design the Network Model

Re-Design the Network Model

- In recurrent neural networks, updating across fewer prior time steps during training, called

truncated Backpropagationthrough time, may reduce the exploding gradient problem.

![]() Using LSTM

Using LSTM

- Exploding gradients can be reduced by using the

Long Short-Term Memory(LSTM) memory units and perhaps relatedgated-typeneuron structures. Adopting LSTM memory units is a new best practice for recurrent neural networks for sequence prediction.

![]() Use Gradient Clipping

Use Gradient Clipping

- Exploding gradients can still occur in very deep Multilayer Perceptron networks with

- Large batch size

- LSTMs with very long input sequence lengths.

- If exploding gradients are still occurring, you can check for and limit the size of gradients during the training of your network. This is called

gradient clipping.

clipping gradients if their norm exceeds a given threshold

![]() Use Weight Regularization

Use Weight Regularization

Resource:

How does LSTM help prevent the vanishing (and exploding) gradient problem in a recurrent neural network?

There are two factors that affect the magnitude of gradients

- The weights

- The activation functions (or more precisely, their derivatives) that the gradient passes through.

If either of these factors is smaller than 1, then the gradients may vanish in time; if larger than 1, then exploding might happen. For example,- The $tanh$ derivative is $\lt1$ for all inputs except $0$

- Sigmoid is even worse and is always $\leq 0.25$.

In the recurrency of the LSTM, the activation function is the identity function with a derivative of 1.0. So, the backpropagated gradient neither vanishes or explodes when passing through, but remains constant.

The effective weight of the recurrency is equal to the forget gate activation. So, if the forget gate is on (activation close to 1.0), then the gradient does not vanish. Since the forget gate activation is never >1.0, the gradient can’t explode either. So that’s why LSTM is so good at learning long range dependencies.

Solution 1) Use activation functions which have ‘good’ gradient values. Not ZERO over a reasonable amount of range Not that small, Not that big. e.g. ReLu. reference

Solution 2) Use gating(pass or block, or in other words, 1 or 0) function, not activation function. And train the ‘combination’ of all those gates. Doing this, no matter how ‘deep’ your network is, or how ‘long’ the input sequence is, the network can remember those values, as long as those gates are all 1 along the path. <- This is how LSTM/GRU did the job.

The vanishing (and exploding) gradient problem is caused by the repeated use of the recurrent weight matrix in RNN. In LSTM, the recurrent weight matrix is replaced by the identity function in the carousel (carousel means conveyor belt, here it denotes the cell state $C_t$) and controlled by the forget gate. So ignoring the forget gate (which can always be open), the repeated use of the identity function would not introduce the vanishing (and exploding) gradient.

The recent IndRNN(Building A Longer and Deeper RNN) model also addresses the gradient vanishing and exploding problem. It uses learnable recurrent weights but regulated in a way to avoid the gradient vanishing and exploding problem. Compared with LSTM, it is much faster and can be stacked into deep models. Better performance is shown by IndRNN over the traditional RNN and LSTM.

Given that $f$, the forget gate, is the rate at which you want the neural network to forget its past memory, the error signal is propagated perfectly to the previous time step. In many LSTM papers, this is referred to as the linear carousel that prevents the vanish of gradient through many time steps.

Reference:

Why can RNNs with LSTM units also suffer from “exploding gradients”?

In the paper Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks (by Ilya Sutskever, Oriol Vinyals, Quoc V. Le), section “3.4 Training details”, it is stated Although LSTMs tend to not suffer from the vanishing gradient problem, they can have exploding gradients.

TL;DR: LSTM decouples cell state (typically denoted by $C_t$) and hidden layer/output (typically denoted by $h_t$), and only do additive updates to $C_t$, which makes memories in $C_t$ more stable. Thus the gradient flows through $C_t$ is kept and hard to vanish (therefore the overall gradient is hard to vanish). However, other paths may cause gradient explosion.

Detailed Answer: StackExchange

More Detailed Answer: LSTM: A search space odyssey

Preventing Vanishing Gradients with LSTMs

..replace activation function with the gating function….

Well behaved derivated: The biggest culprit in causing our gradients to vanish is that dastardly recursive derivative we need to compute: $\frac{\partial s_j}{\partial s_{j-1}}$ (![]() where $s$ is

where $s$ is cell state, and $j$ is the time step, thus we can write in more meaningful way as $\frac{\partial C_t}{\partial C_{t-1}}$). If only this derivative was well behaved (that is, it doesn’t go to $0$ or $\infty$ (infinity) as we backpropagate through layers) then we could learn long term dependencies!

The original LSTM solution: The original motivation behind the LSTM was to make this recursive derivative have a constant value. If this is the case then our gradients would neither explode or vanish. How is this accomplished? As you may know, the LSTM introduces a separate cell state $C_t$. In the original 1997 LSTM, the value for $C_t$ depends on the previous value of the cell state (i.e $C_{t-1}$) and an update term weighted by the input gate value (for motivation on why the input/output gates are needed, I would check out this great post):

This formulation doesn’t work well because the cell state tends to grow uncontrollably. In order to prevent this unbounded growth, a forget gate was added to scale the previous cell state, leading to the more modern formulation:

One important thing to note is that the values $f_t$, $o_t$, $i_t$, and $\tilde C_t$ are things that the network learns to set (conditioned on the current input and hidden state). Thus, in this way the network learns to decide when to let the gradient vanish, and when to preserve it, by setting the gate values accordingly!

This might all seem magical, but it really is just the result of two main things:

The additive update function for the cell state gives a derivative thats much more

well behaved. The gating functions allow the network to decide how much the gradient vanishes, and can take on different values at each time step. The values that they take on are learned functions of the current input and hidden state.

Resource:

Why Input-Output Gates are needed?

Resource:

Gating in Deep learning

… gating decides how much

cell state$C$ information flows from $C_{t-1}$ to $C_t$

Gating meaning:

Although it can be a complex process and involve multiple gates or regions of interest, the process of gating is simply selecting an area on the scatter plot generated during the flow experiment that decides which cells you continue to analyze and which cells you don’t. reference

TL;DR: the process by which a channel in a cell membrane opens or closes. Dictionary Meaning

In LSTM, gating decides how much cell state information, from previous step, to flow in the next step or not. Thus gating function is different from the Activation function and helps in case of Vanishing Gradient problem.

Reference:

Use of Sigmoid and Tanh

Q: Why using sigmoid and tanh as the activation functions in LSTM or RNN is not problematic but this is not the case in other neural nets?

Commonly, $sigmoid$ and $tanh$ activation functions are problematic (gradient vanishing) in RNN especially when the training algorithm $BPTT$ is utilized. In LSTM, sigmoid and tanh are used to build the $gates$. Because of these gates, the gradient vanishing problem does not exist.

Understand forward and backward with simple Perceptron

- Check the [blog] and it’s implementation and result in the following [notebook]

- Give attention to the intermediate values in the blog and in the code side by side and check they are equal.

Loss Functions in Deep learning

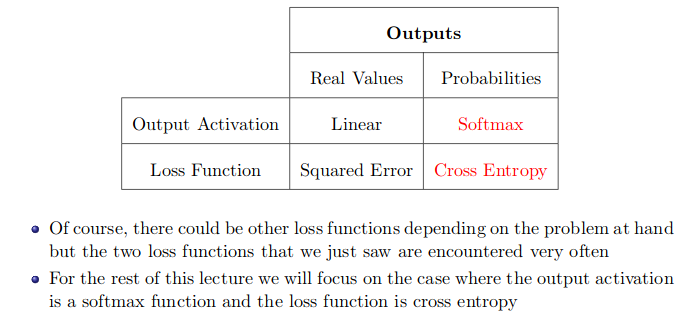

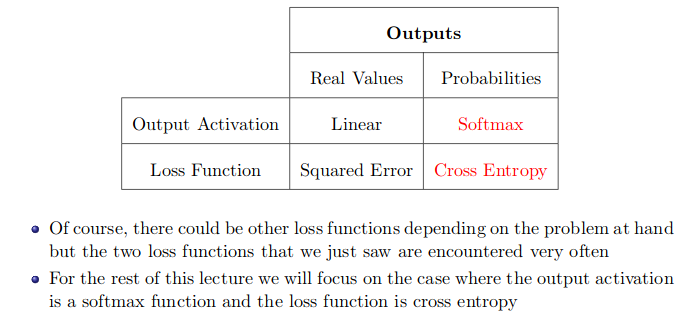

Tell about different loss function, when to use them?

Importantly, the choice of

loss functionis directly related to theactivation functionused in theoutput layerof your neural network. These two design elements are connected.

The choice of cost function is tightly coupled with the choice of output unit. Most of the time, we simply use the

cross-entropybetween thedata distributionand themodel distribution. The choice of how to represent the output then determines the form of the cross-entropy function.

Regression Problem

A problem where you predict a real-value quantity.

Case 1:

-

Output Layer Configuration:One node with a linear activation unit. -

Loss Function:Mean Squared Error (MSE).

Case 2:

-

Output Layer Configuration:One node with a linear activation unit. -

Loss Function:Mean Squared Logarithmic Error (MSLE)

When to use case 2

Mean Squared Logarithmic Error (MSLE) loss function is a variant of MSE, which is defined as above.

- It is usually used when the

true valuesand thepredicted valuesare very big. And therefore, their difference are also very big. In that situation, you generally don’t want to penalizes huge difference between true and predicted to their high value range. - One use case say

sales priceprediction. Here the true value range can be veryskewedwhich affects the prediction as well. Here regularMSEwill heavily penalizes the big differences. But in this scenario it’s wrong because here by default the value ranges are very big i.e. skewed. In this scenario one good approach is take thelog(true_value)and predict that, and by default you have to use theMSLE. - Another usefulness of applying

logis it fixes the skewness and brings it more close to normal distribution.

Binary Classification Problem

-

Output Layer Configuration:One node with a sigmoid activation unit. -

Loss Function:Cross-Entropy, also referred to as Logarithmic loss.

Multi-Class Classification Problem

-

Output Layer Configuration:One node for each class using the softmax activation function. -

Loss Function:Cross-Entropy, also referred to as Logarithmic loss.

In binary classification, where the number of classes M equals 2, cross-entropy can be calculated as:

here the assumption is $y \in [0,1]$

If $M\gt2$ (i.e. multiclass classification), we calculate a separate loss for each class label per observation and sum the result.

Summary

Image Source: From Prof. Mitesh Khapra, Lecture 4, [slide page 95]

References:

- Source MachineLearningMastery

- Source: How_to_be_on_top_0p3_percent_kaggle_competiion

- Blog

- Deep Learning Lecture 4 by Prof. Mitesh khapra

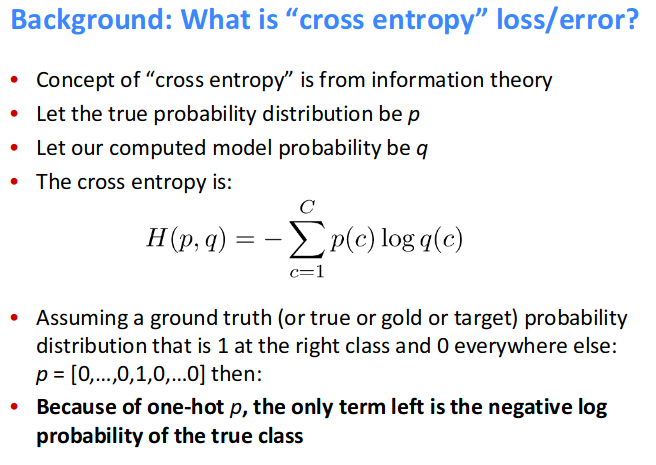

What is cross-entropy loss?

Resource:

NLLLoss implementation nn.NLLLoss()

-

The negative log likelihood loss. It is useful to train a classification problem with

Cclasses. - The

inputgiven through a forward call is expected to contain log-probabilities of each class. - Obtaining log-probabilities in a neural network is easily achieved by adding a

LogSoftmaxlayer in the last layer of your network. You may useCrossEntropyLossinstead, if you prefer not to add an extra layer.

import torch

torch.manual_seed(1)

def NLLLoss(logs, targets):

"""

logs: output of the forward call where logSoftMax()

has been applied at the last layer

"""

out = torch.zeros_like(targets, dtype=torch.float)

for i in range(len(targets)):

out[i] = logs[i][targets[i]]

return -out.sum()/len(out)

x = torch.randn(3, 5)

y = torch.LongTensor([0, 1, 2])

cross_entropy_loss = torch.nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

log_softmax = torch.nn.LogSoftmax(dim=1)

x_log = log_softmax(x)

nll_loss = torch.nn.NLLLoss()

print("Torch CrossEntropyLoss: ", cross_entropy_loss(x, y))

print("Torch NLL loss: ", nll_loss(x_log, y))

print("Custom NLL loss: ", NLLLoss(x_log, y))

# Torch CrossEntropyLoss: tensor(1.8739)

# Torch NLL loss: tensor(1.8739)

# Custom NLL loss: tensor(1.8739)

- For optimized code see the resource below

Remember: In short - CrossEntropyLoss = LogSoftmax + NLLLoss.

Resource:

Different loss function and their pros and cons?

Regression Loss

-

Mean Squared Error Loss: The Mean Squared Error, or MSE, loss is the default loss to use for

regression problems. Mathematically, it is the preferred loss function under the inference framework of maximum likelihood if the distribution of the target variable is Gaussian. - Mean Squared Logarithmic Error Loss: There may be regression problems in which the target value has a spread of values and when predicting a large value, you may not want to punish a model as heavily as mean squared error. Instead, you can first calculate the natural logarithm of each of the predicted values, then calculate the mean squared error. This is called the Mean Squared Logarithmic Error loss, or MSLE for short. It has the effect of relaxing the punishing effect of large differences in large predicted values.

- Mean Absolute Error Loss: On some regression problems, the distribution of the target variable may be mostly Gaussian, but may have outliers, e.g. large or small values far from the mean value. The Mean Absolute Error, or MAE, loss is an appropriate loss function in this case as it is more robust to outliers. It is calculated as the average of the absolute difference between the actual and predicted values.

Image Source: From Prof. Mitesh Khapra, Lecture 4, [slide page 95]

Binary Classification Loss

-

Cross Entropy Loss or Negative Loss Likelihood (NLL): It is the default loss function to use for binary classification problems. It is intended for use with binary classification where the target values are in the set

{0, 1}. Mathematically, it is the preferred loss function under the inference framework of maximum likelihood. It is the loss function to be evaluated first and only changed if you have a good reason.

- Hinge Loss or SVM Loss: An alternative to cross-entropy for binary classification problems is the hinge loss function, primarily developed for use with Support Vector Machine (SVM) models. It is intended for use with binary classification where the target values are in the set {-1, 1}. The hinge loss function encourages examples to have the correct sign, assigning more error when there is a difference in the sign between the actual and predicted class values.

Multi-Class Classification Loss Functions

- Categorical Cross Entropy: It is the default loss function to use for multi-class classification problems. In this case, it is intended for use with multi-class classification where the target values are in the set {0, 1, 3, …, n}, where each class is assigned a unique integer value. Mathematically, it is the preferred loss function under the inference framework of maximum likelihood. It is the loss function to be evaluated first and only changed if you have a good reason.

, where c is the class.

- Sparse Categorical Cross Entropy: A possible cause of frustration when using cross-entropy with classification problems with a large number of labels is the one hot encoding process. For example, predicting words in a vocabulary may have tens or hundreds of thousands of categories, one for each label. This can mean that the target element of each training example may require a one hot encoded vector with tens or hundreds of thousands of zero values, requiring significant memory. Sparse cross-entropy addresses this by performing the same cross-entropy calculation of error, without requiring that the target variable be one hot encoded prior to training.

- Kullback Leibler Divergence Loss: Kullback Leibler Divergence, or KL Divergence for short, is a measure of how one probability distribution differs from a baseline distribution. A KL divergence loss of 0 suggests the distributions are identical. In practice, the behavior of KL Divergence is very similar to cross-entropy. It calculates how much information is lost (in terms of bits) if the predicted probability distribution is used to approximate the desired target probability distribution. As such, the KL divergence loss function is more commonly used when using models that learn to approximate a more complex function than simply multi-class classification, such as in the case of an autoencoder used for learning a dense feature representation under a model that must reconstruct the original input. In this case, KL divergence loss would be preferred. Nevertheless, it can be used for multi-class classification, in which case it is functionally equivalent to multi-class cross-entropy.

Reference:

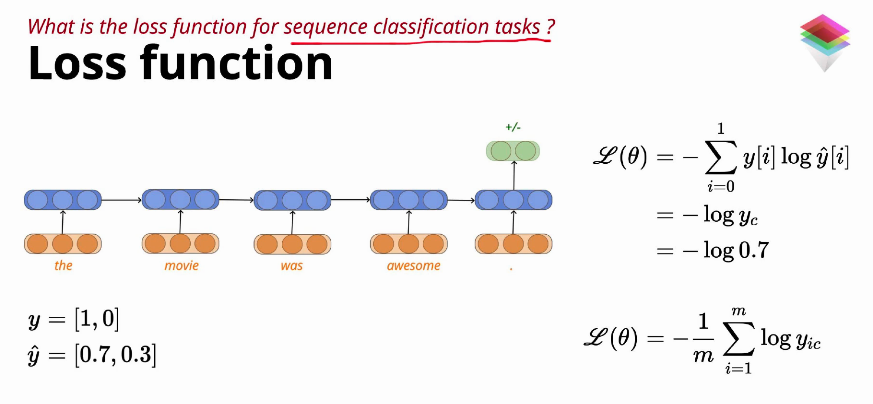

What is the loss function for sequence classification task?

Only finaly time step has generated a classification label.

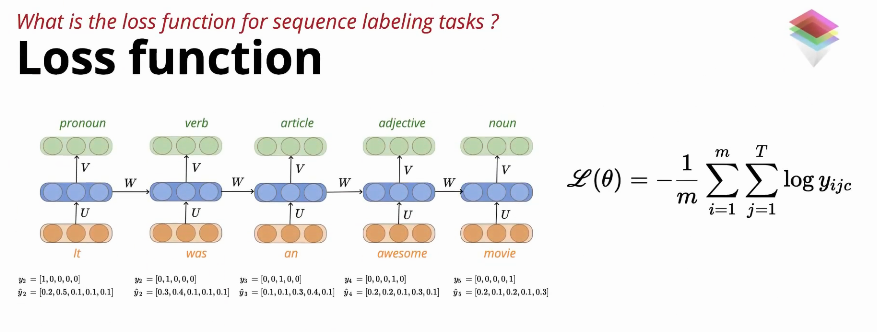

What is the loss function for sequence labelling task?

At each time step there is a label classification, which leads to the double summation.

Resource:

- Deep Learning course from PadhAI, topic: Sequence Model, Lecture: Recurrent Neural Network, Loss Function.

TODO: What is LSTM’s pros and cons?

How does word2vec work?

Reference:

- The Illustrated Word2vec by Jay Alammar

- Intuition & Use-Cases of Embeddings in NLP & beyond, ,talk by Jay Alammar

What is Transfer Learning, BERT, Elmo, UmlFit ?

Reference:

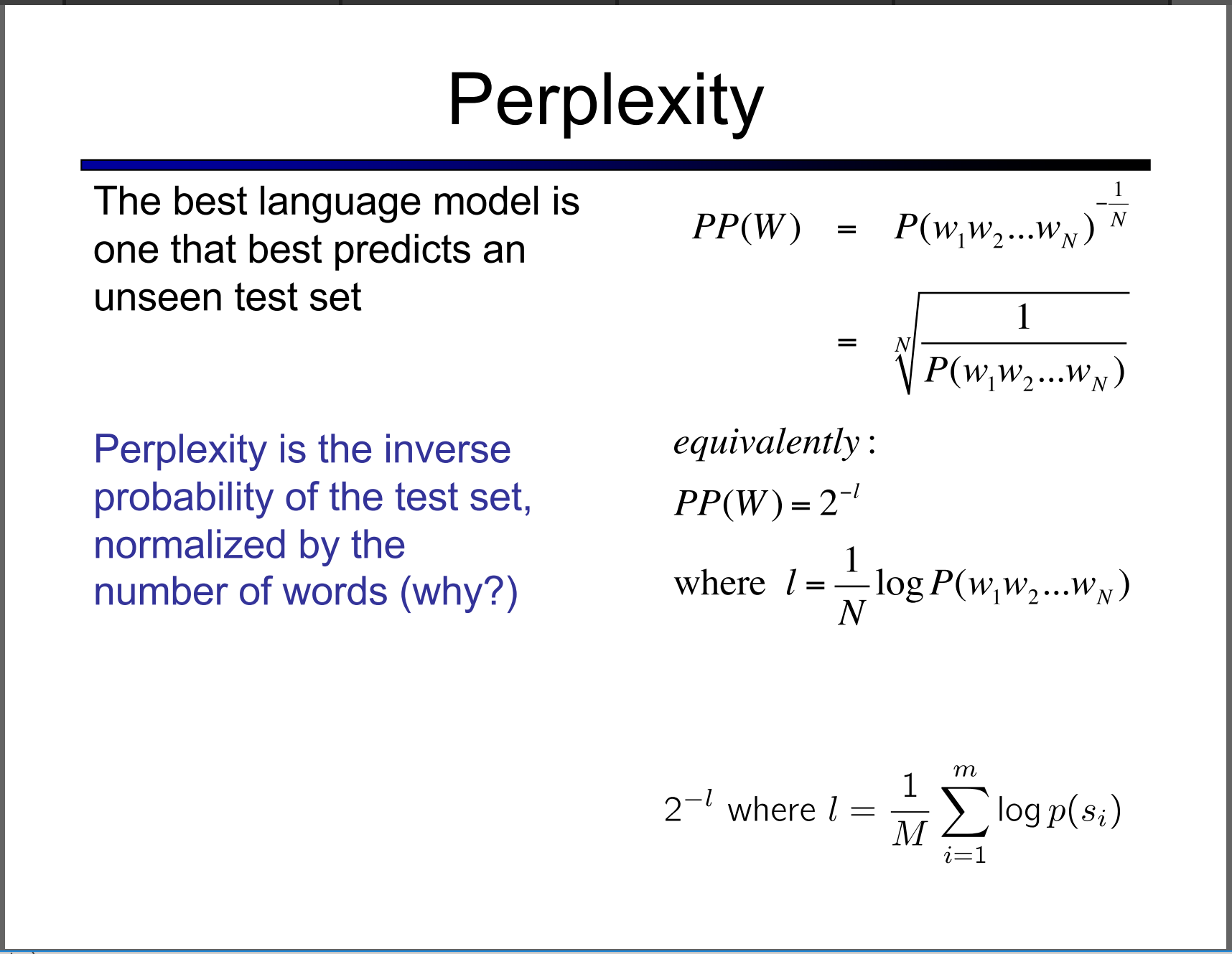

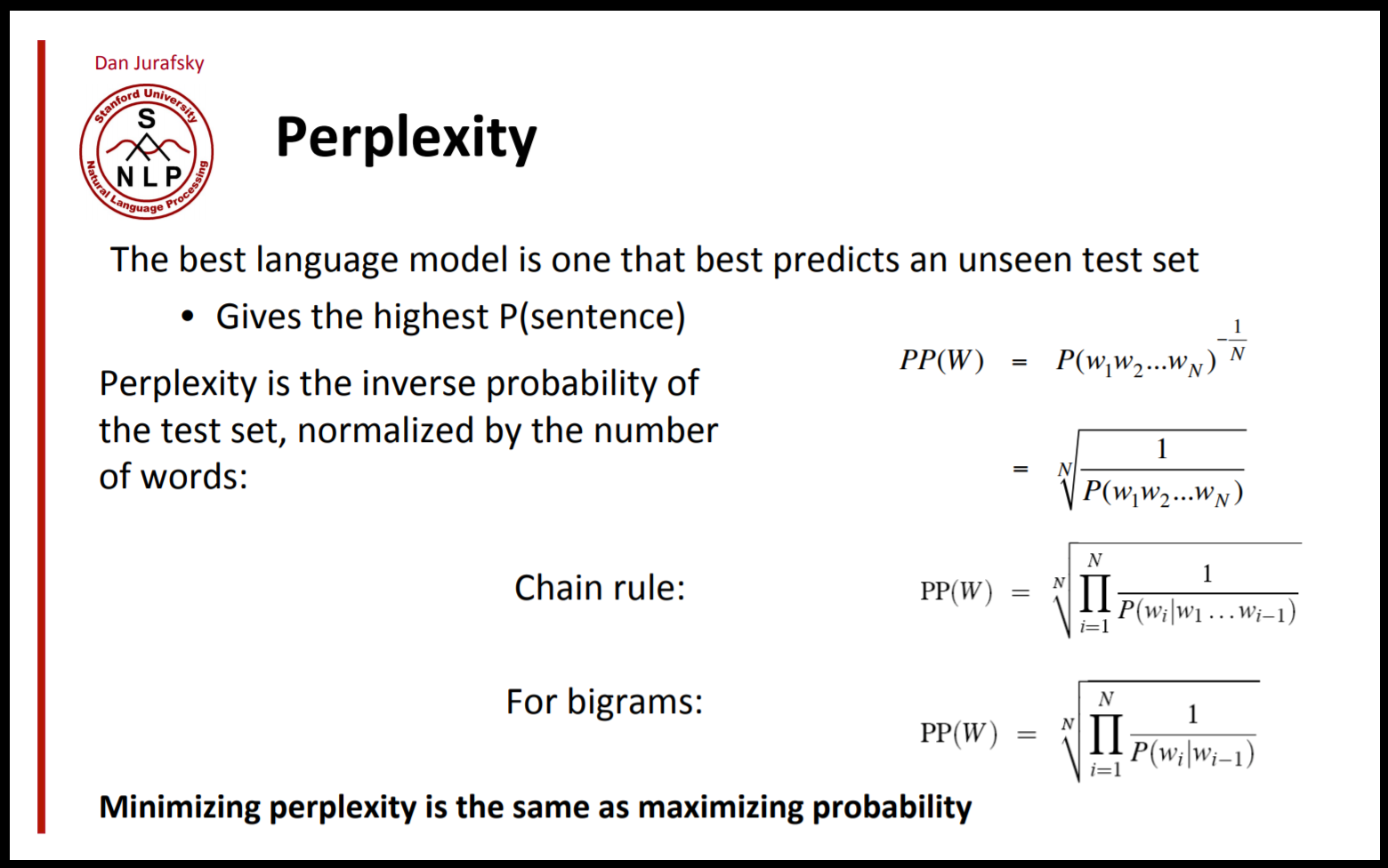

What is model Perplexity?

Perplexity is just an

exponentiation of the entropy!

- In information theory, perplexity is a measurement of how well a probability distribution or probability model predicts a sample. It may be used to

compare probability models. -

A low perplexity indicates the probability distribution is good at predicting the sample. [wiki]

- In natural language processing, perplexity is a way of evaluating language models. A language model is a probability distribution over entire sentences or texts.

But why is perplexity in NLP defined the way it is?

If you look up the perplexity of a discrete probability distribution in Wikipedia, it looks like:

$H(p)$ is the entropy of the distribution $P(x)$ and x is a random variable over all possible events.

Then, perplexity is just an exponentiation of the entropy!

More derivation:

Takeaway:

-

Less entropy (or less disordered system) is favorable over more entropy. As predictable results are preferred over randomness. This is why people say low perplexity is good and high perplexity is bad since the perplexity is the exponentiation of the entropy (and you can safely think of the concept of perplexity as entropy).

-

Why do we use perplexity instead of the entropy? If we think of perplexity as a branching factor (the weighted average number of choices a random variable has), then that number is easier to understand than the entropy.

Reference:

What is BLEU score?

- BLEU, or the

Bilingual Evaluation Understudy, is a score for comparing a candidate translation of text to one or more reference translations. - Although developed for translation, it can be used to evaluate text generated for a suite of natural language processing tasks.

- BLEU uses a

modified form of precisionto compare a candidate translation against multiple reference translations. - The metric modifies simple precision since machine translation systems have been known to generate more words than are in a reference text.

- One problem with BLEU scores is that they tend to favor short translations, which can produce very high precision scores, even using modified precision.

The primary programming task for a BLEU implementor is to compare n-grams of the candidate with the n-grams of the reference translation and count the number of matches. These matches are

position-independent. The more the matches, the better the candidate translation is.

Sentence BLEU Score:

>>> from nltk.translate.bleu_score import sentence_bleu

>>> reference = [['this', 'is', 'a', 'test'], ['this', 'is' 'test']]

>>> candidate = ['this', 'is', 'a', 'test']

>>> score = sentence_bleu(reference, candidate)

>>> print(score)

1.0

Reference:

- Blog by machinelearningmastery

- Paper: BLEU: a Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation

What is GLUE?

GLUE is General Language Understanding Evaluation benchmark, a tool for evaluating and analyzing the performance of models across a diverse range of existing NLU tasks.

- Models are evaluated based on their average accuracy across all tasks.

- GLUE is model-agnostic, but it incentivizes sharing knowledge across tasks because certain tasks have very limited training data.

Similar to GLUE, there is DecaNLP: Natural Language Decathlon

Reference:

Different optimizer Adam, Rmsprop and their pros and cons?

Typically when one sets their learning rate and trains the model, one would only wait for the learning rate to decrease over time and for the model to eventually converge.

However, as the gradient reaches a plateau, the training loss becomes harder to improve. Dauphin et al argue that the difficulty in minimizing the loss arises from saddle points rather than poor local minima.

A saddle point in the error surface. A saddle point is a point where derivatives of the function become zero but the point is not a local extremum on all axes.

Batch gradient descent

Batch gradient descent also doesn’t allow us to update our model online, i.e. with new examples on-the-fly.

Stochastic gradient descent

Batch gradient descent performs redundant computations for large datasets, as it recomputes gradients for similar examples before each parameter update. SGD does away with this redundancy by performing one update at a time. It is therefore usually much faster and can also be used to learn online.

While batch gradient descent converges to the minimum of the basin the parameters are placed in, SGD’s fluctuation, on the one hand, enables it to jump to new and potentially better local minima.

Mini-batch gradient descent

Mini-batch gradient descent finally takes the best of both worlds and performs an update for every mini-batch of n training examples.

Mini-batch gradient descent is typically the algorithm of choice when training a neural network and the term SGD usually is employed also when mini-batches are used.

Momentum

SGD oscillates across the slopes of the ravine while only making hesitant progress along the bottom towards the local optimum.

LEFT: shows a long shallow ravine leading to the optimum and steep walls on the sides. Standard SGD will tend to oscillate across the narrow ravine. RIGHT: Momentum is one method for pushing the objective more quickly along the shallow ravine.

The momentum term $\gamma$ is usually set to 0.9 or a similar value.

Essentially, when using momentum, we push a ball down a hill. The ball accumulates momentum as it rolls downhill, becoming faster and faster on the way (until it reaches its terminal velocity if there is air resistance, i.e. $\gamma \lt 1$). The same thing happens to our parameter updates: The momentum term increases for dimensions whose gradients point in the same directions and reduces updates for dimensions whose gradients change directions. As a result, we gain faster convergence and reduced oscillation.

Nesterov accelerated gradient (NAG)

However, a ball that rolls down a hill, blindly following the slope, is highly unsatisfactory. We’d like to have a smarter ball, a ball that has a notion of where it is going so that it knows to slow down before the hill slopes up again.

- Nesterov accelerated gradient (NAG) [6] is a way to give our momentum term this kind of prescience.

All previous methods use the same learning rate for each of the parameter. Now we want different learning rate for different parameters. Here we go:

Adagrad

It adapts the learning rate to the parameters, performing smaller updates (i.e. low learning rates) for parameters associated with frequently occurring features, and larger updates (i.e. high learning rates) for parameters associated with infrequent features. For this reason, it is well-suited for dealing with sparse data.

$G_{t} \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d}$ here is a diagonal matrix where each diagonal element $i,i$ is the sum of the squares of the gradients w.r.t. $\theta_i$ up to time step $t$, while $\epsilon$ is a smoothing term that avoids division by zero.

As $G_t$ contains the sum of the squares of the past gradients w.r.t. to all parameters $\theta$ along its diagonal, we can now vectorize our implementation by performing a matrix-vector product $\odot$ between $G_t$ and $g_t$:

One of Adagrad’s main benefits is that it eliminates the need to manually tune the learning rate. Most implementations use a default value of 0.01 and leave it at that.

Adadelta

Adadelta is an extension of Adagrad that seeks to reduce its aggressive, monotonically decreasing learning rate.

RMSprop

It is an unpublished, adaptive learning rate method proposed by Geoff Hinton in Lecture 6e of his Coursera Class.

Adam

Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) is another method that computes adaptive learning rates for each parameter. In addition to storing an exponentially decaying average of past squared gradients $v_t$

like Adadelta and RMSprop, Adam also keeps an exponentially decaying average of past gradients $m_t$, similar to momentum. Whereas momentum can be seen as a ball running down a slope, Adam behaves like a heavy ball with friction, which thus prefers flat minima in the error surface. We compute the decaying averages of past and past squared gradients $m_t$ and $v_t$ respectively as follows:

As $m_t$ and $v_t$ are initialized as vectors of 0’s, the authors of Adam observe that they are biased towards zero, especially during the initial time steps, and especially when the decay rates are small.

They counteract these biases by computing bias-corrected first and second moment estimates:

They then use these to update the parameters just as we have seen in Adadelta and RMSprop, which yields the Adam update rule:

Reference:

Autoencoders

Word2Vec

Resource:

Word2Vec - Skip Gram model with negative sampling

You may have noticed that the skip-gram neural network contains a huge number of weights… For our example with 300 features and a vocab of 10,000 words, that’s 3M weights in the hidden layer and output layer each! Training this on a large dataset would be prohibitive, so the word2vec authors introduced a number of tweaks to make training feasible.

The authors of Word2Vec addressed these issues in their second paper with the following two innovations:

-

Subsamplingfrequent words todecrease the number of training examples. - Modifying the optimization objective with a technique they called

Negative Sampling, which causes each training sample toupdate only a small percentage of the model’s weights.

As we discussed, the size of word vocabulary means that our skip-gram neural network has a tremendous number of weights, all of which would be updated slightly by every one of our billions of training samples!

Negative sampling addresses this by having each training sample only modify a small percentage of the weights, rather than all of them. Here’s how it works.

When training the network on the word pair ("fox", "quick"), recall that the "label" or "correct output" of the network is a one-hot vector. That is, for the output neuron corresponding to "quick" to output a 1, and for all of the other thousands of output neurons to output a 0.

With negative sampling, we are instead going to randomly select just a small number of negative words (let’s say 5) to update the weights for. (In this context, a negative word is one for which we want the network to output a 0 for). We will also still update the weights for our positive word (which is the word “quick” in our current example).

Resource

Named Entity Recognition

Resource:

Word embedding - Implementation

Natural language processing systems traditionally treat words as discrete atomic symbols, and therefore ![]()

cat may be represented as Id537 and ![]()

dog as Id143. These encodings are arbitrary, and provide no useful information to the system regarding the relationships that may exist between the individual symbols. This means that the model can leverage very little of what it has learned about ‘cats’ when it is processing data about ‘dogs’.

Word embeddings transform sparse vector representations of words into a dense, continuous vector space, enabling you to identify similarities between words and phrases — on a large scale — based on their context.

Vector space models (VSMs) represent (embed) words in a continuous vector space where semantically similar words are mapped to nearby points ('are embedded nearby each other'). VSMs have a long, rich history in NLP, but all methods depend in some way or another on the Distributional Hypothesis, which states that words that appear in the same contexts share semantic meaning. The different approaches that leverage this principle can be divided into two categories:

-

count-based methods(e.g. Latent Semantic Analysis) -

predictive methods(e.g. neural probabilistic language models).

This distinction is elaborated in much more detail by Baroni et al., but in a nutshell:

- Count-based methods compute the statistics of how often some word co-occurs with its neighbor words in a large text corpus, and then map these count-statistics down to a small, dense vector for each word.

- Predictive models directly try to predict a word from its neighbors in terms of learned small, dense embedding vectors (considered parameters of the model).

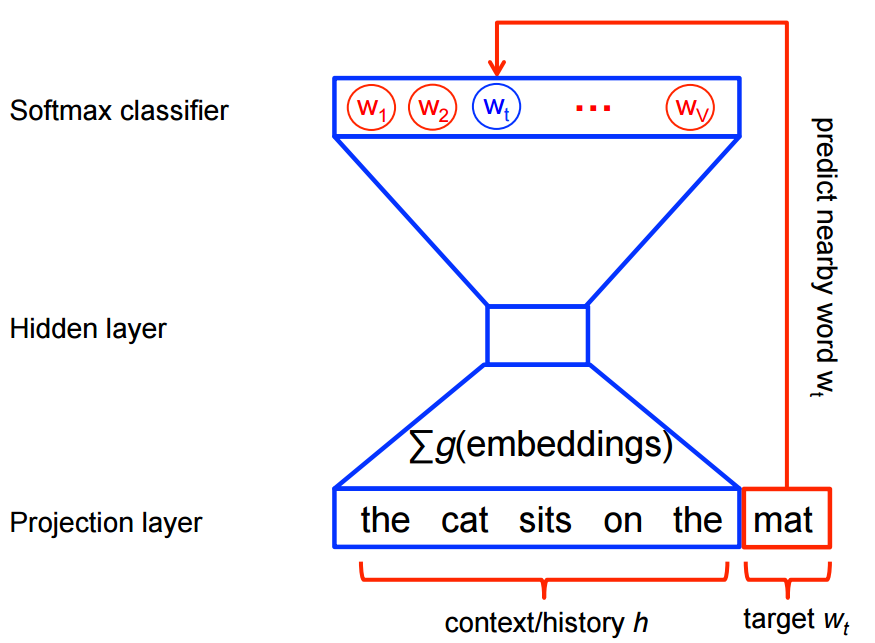

Neural probabilistic language models are traditionally trained using the maximum likelihood (ML) principle to maximize the probability of the next word $w_t$ (for “target”) given the previous words $h$ (for “history”) in terms of a softmax function

where $score(w_t,h)$ computes the compatibility of word $w_t$ with the context $h$ (a dot product is commonly used). We train this model by maximizing its log-likelihood on the training set, i.e. by maximizing

This yields a properly normalized probabilistic model for language modeling. However this is very expensive, because we need to compute and normalize each probability using the score for all other $V$ words $w’$ in the current context $h$ , at every training step.

Word2vec = Implementation

Word2vec is a particularly computationally-efficient predictive model for learning word embeddings from raw text. It comes in two flavors:

- Continuous Bag-of-Words model (CBOW)

- Skip-Gram model (Section 3.1 and 3.2 in Mikolov et al.).

Algorithmically, these models are similar, except that CBOW predicts target words (e.g. mat) from a sliding window of a source context words (the cat sits on the), while the skip-gram does the inverse and predicts source context-words from the target words.

This inversion might seem like an arbitrary choice, but statistically it has the effect that CBOW smoothes over a lot of the distributional information (by treating an entire context as one observation). For the most part, this turns out to be a useful thing for smaller datasets. However, skip-gram treats each context-target pair as a new observation, and this tends to do better when we have larger datasets. We will focus on the skip-gram model in the rest of this tutorial.

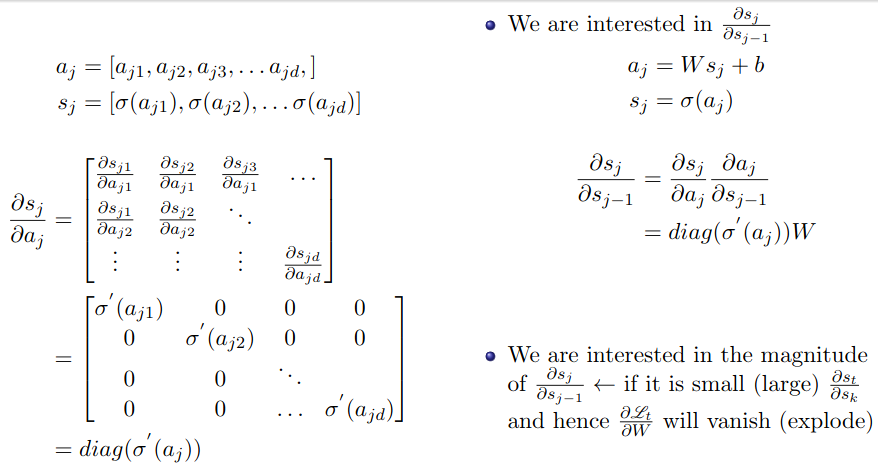

![]() For feature learning in word2vec, we do not need a full probabilistic model. The CBOW and skip-gram models are instead trained using a binary classification objective (logistic regression) to discriminate the real target words $w_t$ from $k$ imaginary (noise/negative samples) words $\tilde w$, in the same context. We illustrate this below for a CBOW model. For skip-gram the direction is simply inverted.

For feature learning in word2vec, we do not need a full probabilistic model. The CBOW and skip-gram models are instead trained using a binary classification objective (logistic regression) to discriminate the real target words $w_t$ from $k$ imaginary (noise/negative samples) words $\tilde w$, in the same context. We illustrate this below for a CBOW model. For skip-gram the direction is simply inverted.

Google’s word2vec is one of the most widely used implementations due to its training speed and performance. Word2vec is a predictive model, which means that instead of utilizing word counts à la latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), it is trained to predict a target word from the context of its neighboring words. The model first encodes each word using one-hot-encoding, then feeds it into a hidden layer using a matrix of weights; the output of this process is the target word. The word embedding vectors are actually the weights of this fitted model. To illustrate, here’s a simple visual:

Resource:

LSTM demystified

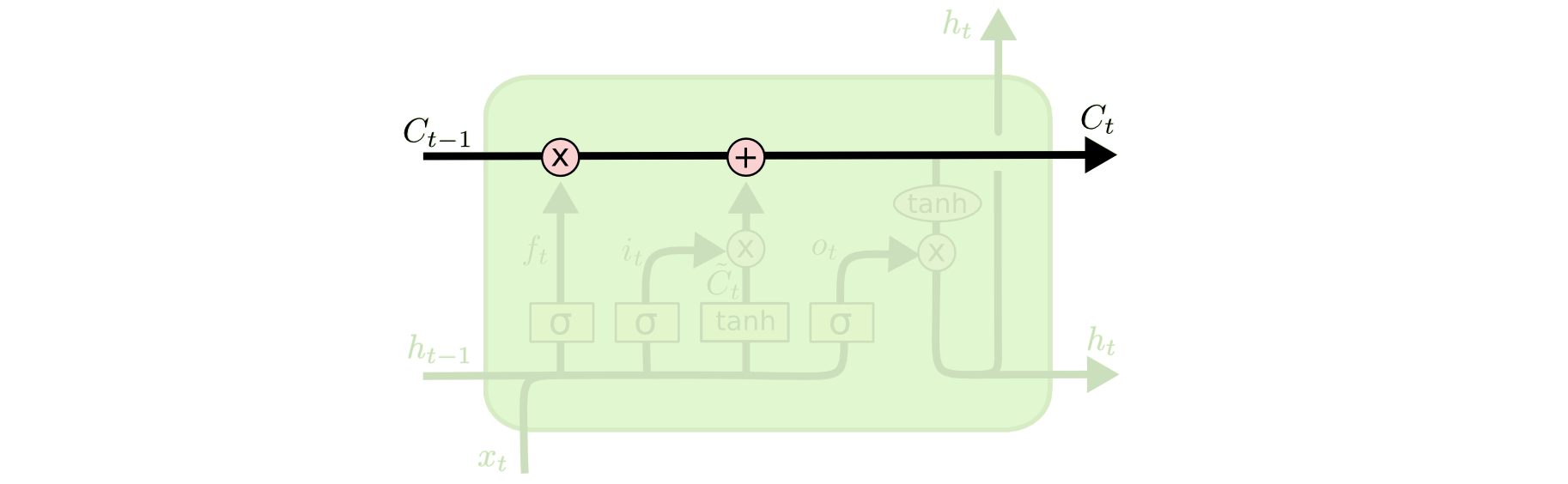

Core Idea: The key to LSTMs is the cell state, the horizontal line running through the top of the diagram. The cell state is kind of like a conveyor belt. It runs straight down the entire chain, with only some minor linear interactions. It’s very easy for information to just flow along it unchanged.

The LSTM does have the ability to remove or add information to the cell state, carefully regulated by structures called gates. It has forget gate, input gate and output gate.

Forget Gate:

It controls how much old information (or old memory or state) you want to retain or not. $f_t\in(0,1)$ and thus it maintains a proportion of old memory.

Input Gate:

The next step is to decide what new information we’re going to store in the cell state. This has two parts.

- First, a sigmoid layer called the “input gate layer” decides which values we’ll update.

- Second, a tanh layer creates a vector of new candidate values, $\tilde{C}_t$, that could be added to the state. In the next step, we’ll combine these two to create an update to the state.

Cell Update:

We multiply the old state by ft, forgetting the things we decided to forget earlier. Then we add $i_t*\tilde{C}_t$. This is the new candidate values, scaled by how much we decided to update each state value.

Output Gate:

Finally, we need to decide what we’re going to output. This output will be based on our cell state, but will be a filtered version.

- First, we run a sigmoid layer which decides what parts of the cell state we’re going to output.

- Second, we put the cell state through tanh (to push the values to be between −1 and 1) and multiply it by the output of the sigmoid gate, so that we only output the parts we decided to.

Resource:

Why the input/output gates are needed in LSTM?

Vanishing Gradient Problem in general

What is vanishing gradient problem in RNN?

The derivative $\frac{\partial h_{k}}{\partial h_1}$ ($\frac{\partial s_{t}}{\partial s_1}$ or $\frac{\partial C_{t}}{\partial C_1}$, all same) is essentially telling us how much our hidden state at time $t=k$ will change when we change the hidden state at time $t=1$ by a little bit…

If you don’t already know, the vanishing gradient problem arises when, during backprop, the error signal used to train the network exponentially decreases the further you travel backwards in your network. The effect of this is that the layers closer to your input don’t get trained.

To understand why LSTMs help, we need to understand the problem with vanilla RNNs. In a vanilla RNN, the hidden vector and the output is computed as such:

To do backpropagation through time to train the RNN, we need to compute the gradient of $E$ with respect to $W_R$. The overall error gradient is equal to the sum of the error gradients at each time step. For step $t$, we can use the multivariate chain rule to derive the error gradient as:

Now everything here can be computed pretty easily except the term $\frac{\partial h_t}{\partial h_i}$, which needs another chain rule application to compute:

Now let us look at a single one of these terms by taking the derivative of $h_{k+1}$ with respect to $h_k$ (where $diag$ turns a vector into a diagonal matrix):

Thus, if we want to backpropagate through $k$ timesteps, this gradient will be :

![]() $h_t$ is the hidden state, in other books or resource it’s also shown as $s_t$ or $C_t$. Thus $\frac{\partial h_{t+1}}{\partial h_t}$ is same as $\frac{\partial s_{t+1}}{\partial s_t}$ or $\frac{\partial C_{t+1}}{\partial C_t}$

$h_t$ is the hidden state, in other books or resource it’s also shown as $s_t$ or $C_t$. Thus $\frac{\partial h_{t+1}}{\partial h_t}$ is same as $\frac{\partial s_{t+1}}{\partial s_t}$ or $\frac{\partial C_{t+1}}{\partial C_t}$

As shown in this paper, if the dominant eigenvalue of the matrix $W_R$ is greater than 1, the gradient explodes. If it is less than 1, the gradient vanishes.2 The fact that this equation leads to either vanishing or exploding gradients should make intuitive sense. Note that the values of $f’(x)$ will always be less than 1. So if the magnitude of the values of $W_R$ are too small, then inevitably the derivative will go to 0. The repeated multiplications of values less than one would overpower the repeated multiplications of $W_R$ . On the contrary, make $W_R$ too big and the derivative will go to infinity since the exponentiation of $W_R$ will overpower the repeated multiplication of the values less than 1. In practice, the vanishing gradient is more common, so we will mostly focus on that.

![]() The derivative $\frac{\partial h_{k}}{\partial h_1}$ ($\frac{\partial s_{t}}{\partial s_1}$ or $\frac{\partial C_{t}}{\partial C_1}$) is essentially telling us how much our hidden state at time $t=k$ will change when we change the hidden state at time $t=1$ by a little bit.

The derivative $\frac{\partial h_{k}}{\partial h_1}$ ($\frac{\partial s_{t}}{\partial s_1}$ or $\frac{\partial C_{t}}{\partial C_1}$) is essentially telling us how much our hidden state at time $t=k$ will change when we change the hidden state at time $t=1$ by a little bit.

![]() According to the above math, if the gradient vanishes it means the earlier hidden states have no real effect on the later hidden states, meaning no long term dependencies are learned! This can be formally proved, and has been in many papers, including the original LSTM paper.

According to the above math, if the gradient vanishes it means the earlier hidden states have no real effect on the later hidden states, meaning no long term dependencies are learned! This can be formally proved, and has been in many papers, including the original LSTM paper.

Reference:

How does LSTM solve vanishing gradient problem?

the vanishing gradient problem arises when, during backprop, the error signal used to train the network exponentially decreases the further you travel backwards in your network. The effect of this is that the layers closer to your input don’t get trained. In the case of RNNs (which can be unrolled and thought of as feed forward networks with shared weights) this means that you don’t keep track of any long term dependencies. This is kind of a bummer, since the whole point of an RNN is to keep track of long term dependencies. The situation is analogous to having a video chat application that can’t handle video chats!

LSTM Equation Reference: Quickly, here is a little review of the LSTM equations, with the biases left off

- $f_t=\sigma(W_f[h_{t-1},x_t])$

- $i_t=\sigma(W_i[h_{t-1},x_t])$

- $o_t=\sigma(W_o[h_{t-1},x_t])$

- $\widetilde{C}t = \tanh(W_C[h{t-1},x_t])$

- $C_t=f_t \odot C_{t-1} + i_t \odot \widetilde{C}_t$

- $h_t=o_t \odot tanh(C_t)$

As we can see above (previous question), the biggest culprit in causing our gradients to vanish is that dastardly recursive derivative we need to compute: $\frac{\partial h_t}{\partial h_i}$. If only this derivative was ‘well behaved’ (that is, it doesn’t go to 0 or infinity as we backpropagate through layers) then we could learn long term dependencies!

The original LSTM solution: The original motivation behind the LSTM was to make this recursive derivative have a constant value. If this is the case then our gradients would neither explode or vanish. How is this accomplished? As you may know, the LSTM introduces a separate cell state $C_t$. In the original 1997 LSTM, the value for $C_t$ depends on the previous value of the cell state and an update term weighted by the input gate value.

This formulation doesn’t work well because the cell state tends to grow uncontrollably. In order to prevent this unbounded growth, a forget gate was added to scale the previous cell state, leading to the more modern formulation:

A common misconception: Most explanations for why LSTMs solve the vanishing gradient state that under this update rule, the recursive derivative is equal to 1 (in the case of the original LSTM) or f (in the case of the modern LSTM)3 and is thus well behaved! One thing that is often forgotten is that f, i, and $\widetilde{C}_t$ are all functions of $C_t$, and thus we must take them into consideration when calculating the gradient.

The reason for this misconception is pretty reasonable. In the original LSTM formulation in 1997, the recursive gradient actually was equal to 1. The reason for this is because, in order to enforce this constant error flow, the gradient calculation was truncated so as not to flow back to the input or candidate gates. So with respect to $C_{t-1}$ they could be treated as constants. In fact truncating the gradients in this way was done up till about 2005, until the publication of this paper by Alex Graves. Since most popular neural network frameworks now do auto differentiation, its likely that you are using the full LSTM gradient formulation too! So, does the above argument about why LSTMs solve the vanishing gradient change when using the full gradient? The answer is no, actually it remains mostly the same. It just gets a bit messier.

Looking at the full LSTM gradient: To understand why nothing really changes when using the full gradient, we need to look at what happens to the recursive gradient when we take the full gradient. For the derivation check this link.

Note: One important thing to note is that the values $f_t$, $o_t$, $i_t$, and $\widetilde{C}_t$ are things that the network learns to set (conditioned on the current input and hidden state). Thus, in this way the network learns to decide when to let the gradient vanish, and when to preserve it, by setting the gate values accordingly!

This might all seem magical, but it really is just the result of two main things:

- The additive update function for the cell state gives a derivative thats much more ‘well behaved’

- The gating functions allow the network to decide how much the gradient vanishes, and can take on different values at each time step. The values that they take on are learned functions of the current input and hidden state.

There is still a chance of gradient vanishing, but the model would regulate its forget gate value to prevent that from happening?

Yes this is correct. If the model is dumb and always sets its forget gate to a low value, then the gradient will vanish. Since the forget gate value is a learnable function, we hope that it learns to regulate the forget gate in a way that improves task performance

How does this prevent gradient explosion?

From my understanding gradient clipping is applied to present that from happening.

This does not really help with gradient explosions, if your gradients are too high there is little that the LSTM gating functions can do for you. There are two standard methods for preventing exploding gradients: Hope and pray that you don’t get them while training, or use gradient clipping. The latter has a greater success rate, however I have had some success with the former, YMMV.

How does CNN solve vanishing gradient problem?

RNNs unfolded are deep in common application scenarios, thus prone to severer vanishing gradient problems. CNNs in typical application scenarios are shallower, but still suffer from the same problem with gradients.

The most recommended approaches to overcome the vanishing gradient problem are:

- Layerwise pre-training

- Choice of the activation function

You may see that the state-of-the-art deep neural network for computer vision problem (like the ImageNet winners) have used convolutional layers as the first few layers of the their network, but it is not the key for solving the vanishing gradient. The key is usually training the network greedily layer by layer. Using convolutional layers have several other important benefits of course. Especially in vision problems when the input size is large (the pixels of an image), using convolutional layers for the first layers are recommended because they have fewer parameters than fully-connected layers and you don’t end up with billions of parameters for the first layer (which will make your network prone to overfitting).

However, it has been shown (like this paper) for several tasks that using Rectified linear units alleviates the problem of vanishing gradients (as oppose to conventional sigmoid functions).

Reference:

How can you cluster documents in unsupervised way?

How do you find the similar documents related to some query sentence/search?

- Simplest apporach is to do tf-idf of both documents and query, and then measure cosine distance (i.e., dot product)

- On top of that, if you use SVD/PCA/LSA on the tfidf matrix, it should further improve results.

- link

Explain TF-IDF?

What is word2vec? What is the cost function for skip-gram model(k-negative sampling)?

Reference:

How can I design a chatbot ?

Exercise

- How did you perform language identification from text sentence ? (As in my CV)

-

- How does you represent the symbolic chinese or japanese alphabets here ?

- Can I develop a chatbot with RNN providing a intent and response pair in input ?

- Suppose I developed a chatbot with RNN/LSTMs on Reddit dataset.

- It gives me 10 probable responses ?

- How can I choose the best reply Or how can I eliminate others replies ?**

- How do you perform text classification ?

- How can you make sure to learn a context !! Well its not possible with TF-IDF ?

- I told him about taking n-grams say n = 1, 2, 3, 4 and concatenating tf-idf of them to make a long count vector ? Okay that is the baseline people start with ? What can you do more with machine learning ? (I tried suggesting LSTM with word2vec or 1D-CNN with word2vec for classification but he wanted improvements in machine learning based methods :-|

- What is the range of sigmoid function ?

- Text classification method. How will you do it ?

- Explain Tf-Idf ? What is the drawback of Tf-Idf ? How do you overcome it ?

- What are bigrams & Tri-grams ? Explain with example of Tf-Idf of bi-grams & trigrams with a text sentence.

- What is an application of word2vec ? Example.

-

How does LSTM work ? How can it remember the context ?

- Must Watch: CS231n by Karpathy in 2016 course and Justin in 2017 course.

- How did you perform language identification ? What were the feature ?

- How did you model classifiers like speech vs music and speech vs non-speech ?

- How can deep neural network be applied in these speech analytics applications ?

- How autoencoder works?