Survey - Natural Language Understanding (NLU - Part 2)

Content

- Content

- NLU Task: Relation Extraction using distant supervision

- Entity Extraction

- Problem formulation

- Natural Language Inference (NLI)

- Language Grounding

- Evaluation

Quick Refresher on Natural Language Understanding

NLU Task: Relation Extraction using distant supervision

- Output of the task is a

discrete objectrather than a numeric value.

Core Reading

- Section 18.2.3 and 18.2.4 Relation extraction by Bootstrapping and Distant Supervision - Book by Jurafsky, 3rd ed

-

Distant supervision for relation extraction without labeled data - Mintz et al. ACL2009

- Learning Syntactic Patterns for Automatic Hypernym Discovery - Snow et al. NIPS2005

- Snorkel

-

Stanford: Notebook Relation Extraction Part 1

Overview

This notebook illustrates an approach to relation extraction using distant supervision. It uses a simplified version of the approach taken by Mintz et al. in their 2009 paper, Distant supervision for relation extraction without labeled data. Read the paper. Must.

The task of relation extraction

Relation extraction is the task of extracting from natural language text relational triples such as:

(founders, SpaceX, Elon_Musk)(has_spouse, Elon_Musk, Talulah_Riley)(worked_at, Elon_Musk, Tesla_Motors)

If we can accumulate a large knowledge base (KB) of relational triples, we can use it to power question answering and other applications.

Building a KB manually is slow and expensive, but much of the knowledge we’d like to capture is already expressed in abundant text on the web. The aim of relation extraction, therefore, is to accelerate the construction of new KBs — and facilitate the ongoing curation of existing KBs — by extracting relational triples from natural language text.

- Huge number of human knowledge can be expressed in this form.

- Microsoft’s KB

satoripowers Bing Search.

What is WordNet?

- It’s a knowledge base of

lexical semantic relation. Where role of entities are played bywordsorsynsets. And the relation between them arehypernym,synonymorantonymrelation.

Supervised learning:

Effective relation extraction will require applying machine learning methods. The natural place to start is with supervised learning. This means training an extraction model from a dataset of examples which have been labeled with the target output. The difficulty with the fully-supervised approach is the cost of generating training data. Because of the great diversity of linguistic expression, our model will need lots and lots of training data: at least tens of thousands of examples, although hundreds of thousands or millions would be much better. But labeling the examples is just as slow and expensive as building the KB by hand would be.

Distant supervision

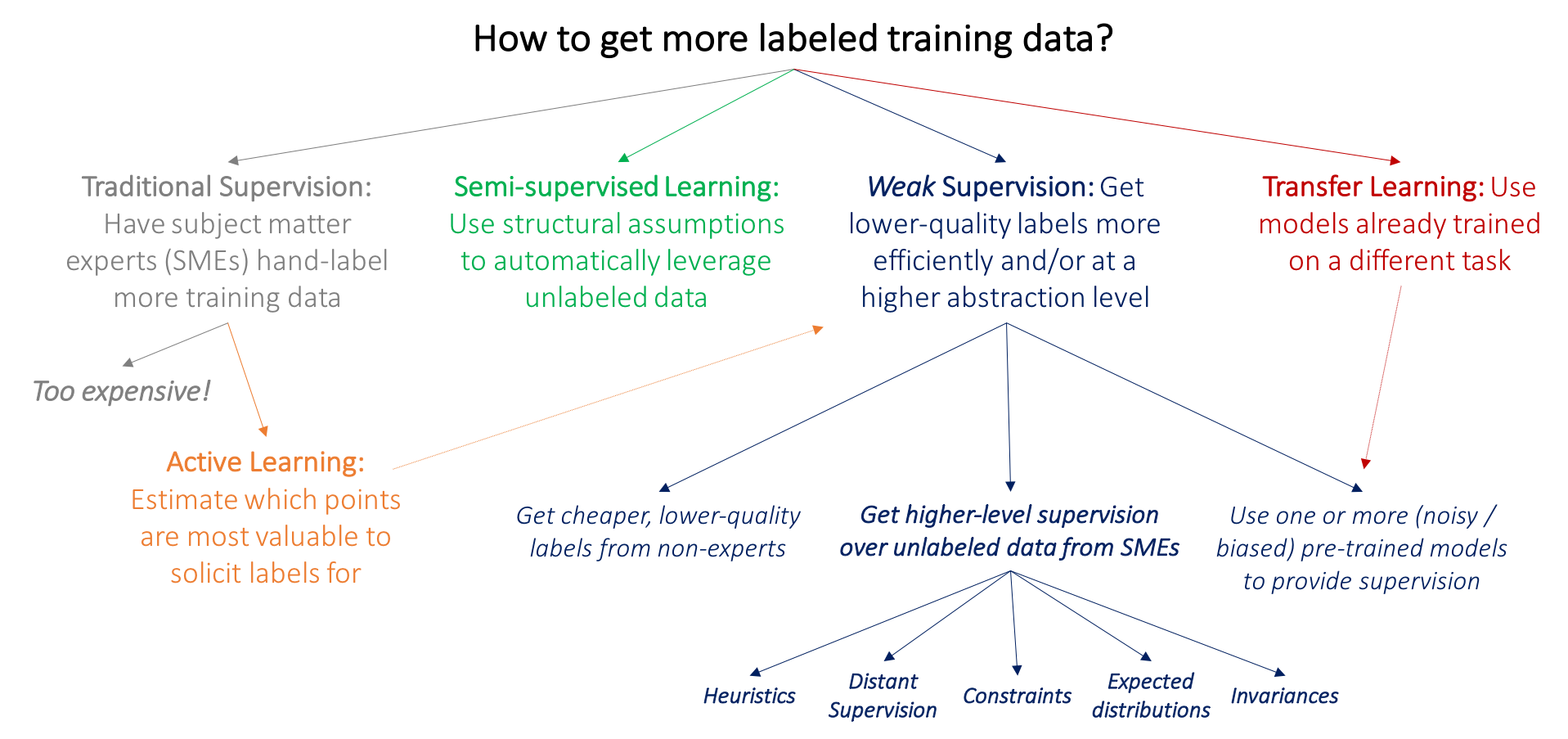

- *Distant Supervision is a type of Weak Supervision

The goal of distant supervision is to capture the

benefits of supervised learning without paying the cost of labeling training data.

Instead of labeling extraction examples by hand, we use existing relational triples (SME: subject matter expert) to automatically identify extraction examples in a large corpus. For example, if we already have in our KB the relational triple (founders, SpaceX, Elon_Musk), we can search a large corpus for sentences in which “SpaceX” and “Elon Musk” co-occur, make the (unreliable!) assumption: that all the sentences express the founder relation, and then use them as training data for a learned model to identify new instances of the founder relation — all without doing any manual labeling.

This is a powerful idea, but it has two limitations.

- Some of the sentences in which “SpaceX” and “Elon Musk” co-occur will not express the founder relation — like the BFR example:

“Billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk announced the latest addition to the SpaceX arsenal: the ‘Big F—ing Rocket’ (BFR)”

By making the blind assumption that all such sentences do express the founder relation, we are essentially injecting noise into our training data, and making it harder for our learning algorithms to learn good models. Distant supervision is effective in spite of this problem because it makes it possible to leverage vastly greater quantities of training data, and the benefit of more data outweighs the harm of noisier data.

- We need an existing KB to start from. We can only train a model to extract new instances of the founders relation if we already have many instances of the founders relation. Thus, while distant supervision is a great way to extend an existing KB, it’s not useful for creating a KB containing new relations from scratch.

Entity Extraction

- While extracting entities, direction matters.

corpus.show_examples_for_pair('Elon_Musk', 'Tesla_Motors')

corpus.show_examples_for_pair('Tesla_Motors', 'Elon_Musk')

Check both directions when we’re looking for examples contains a specific pair of entities.

- Connect the

corpuswith theknowledge base. The corpus tells nothing except the english words.

“…Elon Musk is the founder of Tesla Motors…”

To get the information from the free text, connect with the knowledge base.

Knowledge Base

For any entity extraction work, you need to have a Knowledge Base (KB). Earlier there was the knowledge base Freebase. Unfortunately, Freebase was shut down in $2016$, but the Freebase data is still available from various sources and in various forms. Check the Freebase Easy data dump.

How the knowledge base looks like?

The KB is a collection of relational triples, each consisting of a relation, a subject, and an object. For example, here are three triples from the KB:

- The relation is one of a handful of predefined constants, such as place_of_birth or has_spouse.

- The subject and object are entities represented by Wiki IDs (that is, suffixes of Wikipedia URLs).

The freebase kowledge base stats:

- 45,884 KB triples

- 16 types of relations

Example:

for rel in kb.all_relations:

print(tuple(kb.get_triples_for_relation(rel)[0]))

('adjoins', 'France', 'Spain')

('author', 'Uncle_Silas', 'Sheridan_Le_Fanu')

('capital', 'Panama', 'Panama_City')

('contains', 'Brickfields', 'Kuala_Lumpur_Sentral_railway_station')

('film_performance', 'Colin_Hanks', 'The_Great_Buck_Howard')

('founders', 'Lashkar-e-Taiba', 'Hafiz_Muhammad_Saeed')

('genre', '8_Simple_Rules', 'Sitcom')

('has_sibling', 'Ari_Emanuel', 'Rahm_Emanuel')

('has_spouse', 'Percy_Bysshe_Shelley', 'Mary_Shelley')

('is_a', 'Bhanu_Athaiya', 'Costume_designer')

('nationality', 'Ruben_Rausing', 'Sweden')

('parents', 'Rosanna_Davison', 'Chris_de_Burgh')

('place_of_birth', 'William_Penny_Brookes', 'Much_Wenlock')

('place_of_death', 'Jean_Drapeau', 'Montreal')

('profession', 'Rufus_Wainwright', 'Actor')

('worked_at', 'Brian_Greene', 'Columbia_University')

Limitation

Note that there is no promise or expectation that this KB is complete.

Not only does the KB contain no mention of many entities from the corpus — even for the entities it does include, there may be possible triples which are true in the world but are missing from the KB. As an example, these triples are in the KB:

# (founders, SpaceX, Elon_Musk)

# (founders, Tesla_Motors, Elon_Musk)

# (worked_at, Elon_Musk, Tesla_Motors)

but this one is not:

# (worked_at, Elon_Musk, SpaceX)

In fact, the whole point of developing methods for automatic relation extraction is to extend existing KBs (and build new ones) by identifying new relational triples from natural language text. If our KBs were complete, we wouldn’t have anything to do.

Joining the corpus and the KB

In order to leverage the distant supervision paradigm, we’ll need to connect information in the corpus with information in the KB. There are two possibilities, depending on how we formulate our prediction problem:

- Use the KB to generate labels for the corpus. If our problem is to classify a pair of entity mentions in a specific example in the corpus, then we can use the KB to provide labels for training examples. Labeling specific examples is how the fully supervised paradigm works, so it’s the obvious way to think about leveraging distant supervision as well. Although it can be made to work, it’s not actually the preferred approach.

- Use the corpus to generate features for entity pairs. If instead our problem is to classify a pair of entities, then we can use all the examples from the corpus where those two entities co-occur to generate a feature representation describing the entity pair. This is the approach taken by Mintz et al. 2009, and it’s the approach we’ll pursue here.

So we’ll formulate our prediction problem such that the

- Input is a pair of entities

- The goal is to predict what relation(s) the pair belongs to.

- The

KBwill provide the labels - The

corpuswill provide the features.

Problem formulation

We need to specify:

- What is the input to the prediction?

- Is it a specific pair of entity mentions in a specific context?

- Or is it a pair of entities, apart from any specific mentions?

- What is the output of the prediction?

- Do we need to predict at most one relation label? (This is

multi-class classification.) - Or can we predict multiple relation labels? (This is

multi-label classification.)

- Do we need to predict at most one relation label? (This is

Multi-label classification

A given pair of entities can belong to more than one relation. In fact, this is quite common in any KB.

dataset.count_relation_combinations()

The most common relation combinations are:

1216 ('is_a', 'profession')

403 ('capital', 'contains')

143 ('place_of_birth', 'place_of_death')

61 ('nationality', 'place_of_birth')

11 ('adjoins', 'contains')

9 ('nationality', 'place_of_death')

7 ('has_sibling', 'has_spouse')

3 ('nationality', 'place_of_birth', 'place_of_death')

2 ('parents', 'worked_at')

1 ('nationality', 'worked_at')

1 ('has_spouse', 'parents')

1 ('author', 'founders')

Multiple relations per entity pair is a commonplace phenomenon.

Solution:

- Binary relevance method : which just factors multi-label classification over $n$ labels into $n$ independent binary classification problems, one for each label. A disadvantage of this approach is that, by treating the binary classification problems as independent, it fails to exploit correlations between labels. But it has the great virtue of simplicity, and it will suffice for our purposes.

Building datasets

We’re now in a position to write a function to build datasets suitable for training and evaluating predictive models. These datasets will have the following characteristics:

Because we’ve formulated our problem as multi-label classification, and we’ll be training separate models for each relation, we won’t build a single dataset. Instead, we’ll build a dataset for each relation, and our return value will be a map from relation names to datasets. The dataset for each relation will consist of two parallel lists:

- A list of

candidate KBTripleswhich combine the given relation with a pair of entities. - A corresponding

list of boolean labelsindicating whether the given KBTriple belongs to the KB.

The dataset for each relation will include KBTriples derived from two sources:

- Positive instances will be drawn from the KB.

- Negative instances will be sampled from unrelated entity pairs, as described above.

![]() Reference:

Reference:

- Blog on Data Programming

- [Section 18.2.3 and 18.2.4 Relation extraction by Bootstrapping - Book by Jurafsky, 3rd ed]

-

Stanford: Notebook Relation Extraction Part 1

-

Stanford Lecture CS224U

Stanford Lecture CS224U

Natural Language Inference (NLI)

Prologue

NLI is interesting compared to Sentiment Analysis, because it has two texts to work with.

- Premise

- Hypothesis

That opens up lots of interesting avenue for modelling. How to model Premise and Hypothesis separately and how to relate them.

- Sentence encoding models

- Chained models

Core Reading

-

Learning Distributed Word Representations for Natural Logic Reasoning - Bowman et al. 2015 AAAI

- Stanford Natural Language Inference (SNLI) Corpus

- Reasoning about Entailment with Neural Attention - Rocktäschel et al. 2015

- A Broad-Coverage Challenge Corpus for Sentence Understanding through Inference - Williams et al. 2018

- Adversarial NLI: A New Benchmark for Natural Language Understanding - Nie et al. 2019

Overview

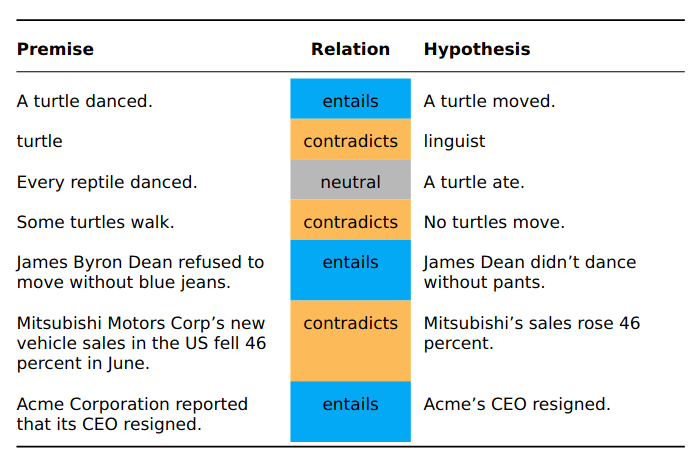

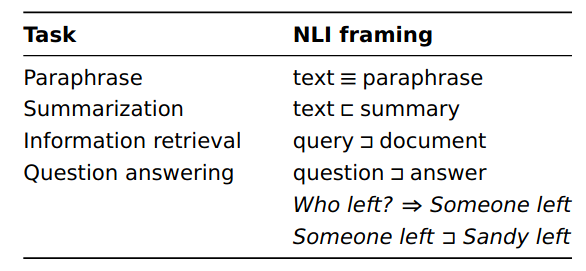

Natural Language Inference (NLI) is the task of predicting the logical relationships between words, phrases, sentences, (paragraphs, documents, …). Such relationships are crucial for all kinds of reasoning in natural language: arguing, debating, problem solving, summarization, and so forth.

Dagan et al. 2006 one of the foundational papers on NLI (also called Recognizing Textual Entailment; RTE), make a case for the generality of this task in NLU:

It seems that major inferences, as needed by multiple applications, can indeed be cast in terms of

**textual entailment**. For example, a QA system has to identify texts that entail (require) a hypothesized answer. […] Similarly, for certain Information Retrieval queries the combination ofsemantic conceptsandrelationsdenoted by thequeryshould be entailed (needed) from relevant retrieved documents. […] In multi-document summarization a redundant sentence, to be omitted from the summary, should be entailed from other sentences in the summary. And in MT evaluation a correct translation should be semantically equivalent to the gold standard translation, and thus both translations should entail each other. Consequently, we hypothesize that textual entailment recognition is a suitable generic task for evaluating and comparing applied semantic inference models. Eventually, such efforts can promote the development of entailment recognitionengineswhich may provide useful generic modules across applications.

Examples:

- Understanding of

common sensereasoning. - Capturing variability in expression.

NLI task formulation

Does the premise justify an inference to the hypothesis?

- Commonsense reasoning, rather than strict logic.

- Focus on local inference steps, rather than long deductive chains.

- Emphasis on variability of linguistic expression

Connection to other tasks

Dataset

They have the same format and were crowdsourced using the same basic methods. However, SNLI is entirely focused on image captions, whereas MultiNLI includes a greater range of contexts.

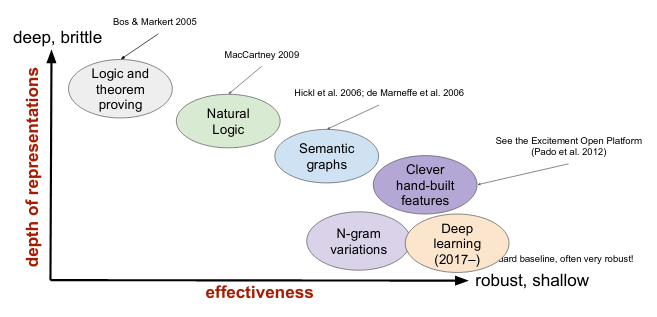

NLI Model Landscape

Combine Dense and Sparse representation

In general hand crafted features are used in linear models and there are deep learning models. Now in deep learning models we use short-dense vectors.

Now how to combine the hand-crafted feature with dense vector.

-

Hand-crafted features are

long and sparsee.g. dimension $20K$ -

Learnt features are

short and densee.g. dimension $50$

Now these 2 can be think of as 2 different word embedding and how to join them.

-

Quick and dirty approach is simple concatenation. But the

long-sparsevector will dominate over theshort-densepart. -

Mature approach: So before concatenation, one good strategy will be to shorten the

long-sparsevector by dimensionality reduction (LSA, PSA) and create a short representation. Which is called model external transformation.

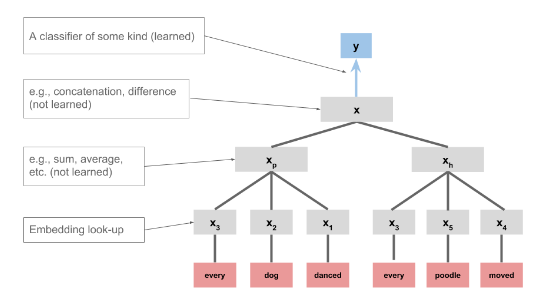

NLI Method: Sentence-encoding models

The hallmark of these is that the premise and hypothesis get their own representation in some sense, and then those representations are combined to predict the label. Bowman et al. 2015 explore models of this form as part of introducing SNLI data.

The feed-forward networks are members of this family of models: each word was represented separately, and the concatenation of those representations was used as the input to the model.

- Different embedding for

PremiseandHypothesis, combine them and model against the target (entails/contradict/neutral) - The embedding can be done in many ways. Simple GloVe lookup

Here’s an implementation of this model where

- The embedding is GloVe.

- The word representations are summed.

- The premise and hypothesis vectors are concatenated.

-

A softmax classifier is used at the top.

- sentence encoding using 2 separate RNN for premise and hypothesis and thus get 2 separate encoding of the 2 sentences as embedding

Dense representations with a shallow neural network

A small tweak to the above is to use a neural network instead of a softmax classifier at the top:

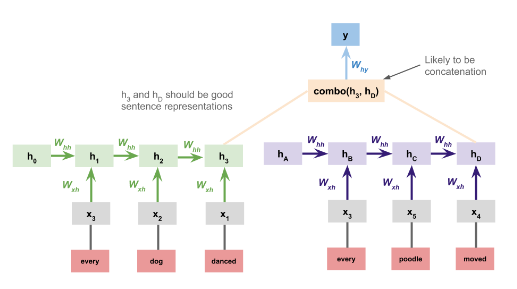

Sentence-encoding RNNs

A more sophisticated sentence-encoding model processes the premise and hypothesis with separate RNNs and uses the concatenation of their final states as the basis for the classification decision at the top:

$h_3$ and $h_d$ are sentence level embedding of premise and hypothesis.

- This RNN representation creates a summary embedding.

- We can also use a

bi-directionalRNN. - But can we join the 2 sentences (premise and hypothesis) and use a single RNN instead of 2 separate RNN. Will that be helpful?

Chained modelis the answer to this.

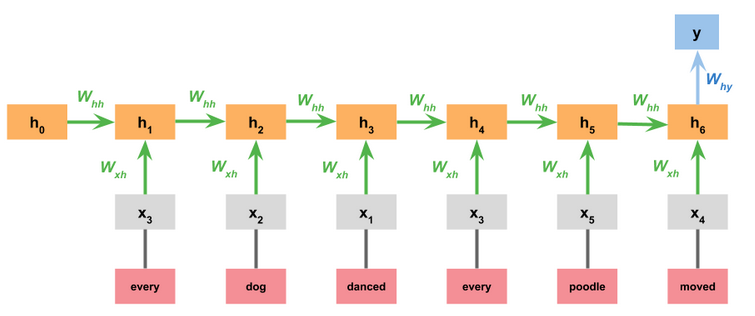

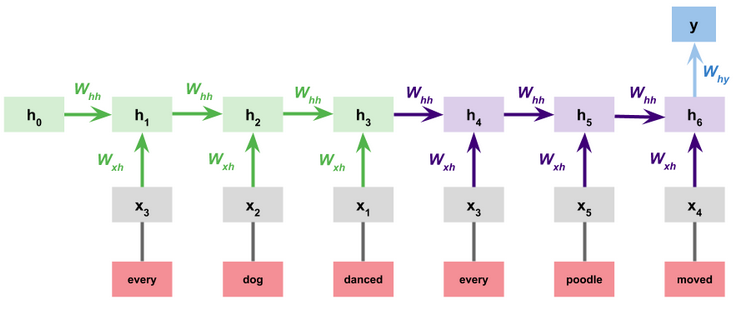

Chained models

The final major class of NLI designs we look at are those in which the premise and hypothesis are processed sequentially, as a pair. These don’t deliver representations of the premise or hypothesis separately. They bear the strongest resemblance to classic sequence-to-sequence models.

Simple RNN

In the simplest version of this model, we just concatenate the premise and hypothesis. The model itself is identical to the one we used for the Stanford Sentiment Treebank:

Separate premise and hypothesis RNNs:

A natural variation on the above is to give the premise and hypothesis each their own RNN:

This greatly increases the number of parameters, but it gives the model more chances to learn that appearing in the premise is different from appearing in the hypothesis. One could even push this idea further by giving the premise and hypothesis their own embeddings as well. One could implement this easily by modifying the sentence-encoder version defined above.

Attention mechanisms:

Many of the best-performing systems in the SNLI leader board use attention mechanisms to help the model learn important associations between words in the premise and words in the hypothesis. I believe Rocktäschel et al. (2015) were the first to explore such models for NLI.

For instance, if puppy appears in the premise and dog in the conclusion, then that might be a high-precision indicator that the correct relationship is entailment.

This diagram is a high-level schematic for adding attention mechanisms to a chained RNN model for NLI:

Sparse feature representations

We begin by looking at models based in sparse, hand-built feature representations. As in earlier units of the course, we will see that these models are competitive: easy to design, fast to optimize, and highly effective.

Feature representations

The guiding idea for NLI sparse features is that one wants to knit together the premise and hypothesis, so that the model can learn about their relationships rather than just about each part separately.

![]() Reference:

Reference:

-

Stanford Notebook on NLI Part 1

- CS224U Youtube Lecture on NLI Part 1

- CS224U Youtube Lecture on NLI Part 2

-

CS224U Notebook on NLI Part 2

Language Grounding

Context

How does language relate to the real world?

From the paper Matuszek et al. IJCAI2018, Grounded language acquisition is concerned with learning the meaning of language as it applies to the physical world. As robots become more capable and ubiquitous, there is an increasing need for non-specialists to interact with and control them, and natural language is an intuitive, flexible, and customizable mechanism for such communication. At the same time, physically embodied agents offer a way to learn to understand natural language in the context of the world to which it refers.

This is perhaps most easily seen in an NLG context in the problem of choosing words to express data. For example,

- How do we map visual data onto colour terms such as “red”

- How do we map

clock timesontotime expressionssuch as “late evening”? - How do we map

geographic regionsontodescriptorssuch as “central Scotland”?

Current progress in this field:

- Generating image descriptions

In the vast majority of cases, the data $\rightarrow$ word mapping depends on context. For example, sticking to temperatures, lets look at hot ![]() . Its meaning depends on (amongst other things)

. Its meaning depends on (amongst other things)

other data (in addition to temperature). For example,

- $30 \degree$C may be hot if humidity is high, but not if humidity is low

-

Expectations and interpretation. For example, $30 \degree$C may be hot in Antartica

, but not in the Sahara desert

, but not in the Sahara desert  .

. -

Individual speakers: Even in the same location, a Scottish person may call $30 \degree$C hot, while a Vietnamese

does not.

does not. - Discourse context: If a previous speaker has used hot to mean $30 \degree$C, other speakers may align to this usage and do likewise

-

Perceived colour depends on

visual context(lighting conditions, nearby objects) as well as the RGB value of a set of pixels -

Perceived time in expressions such as

by eveningcan depend onseasonandsunsettime as well as the clock time being communicated.

Core reading

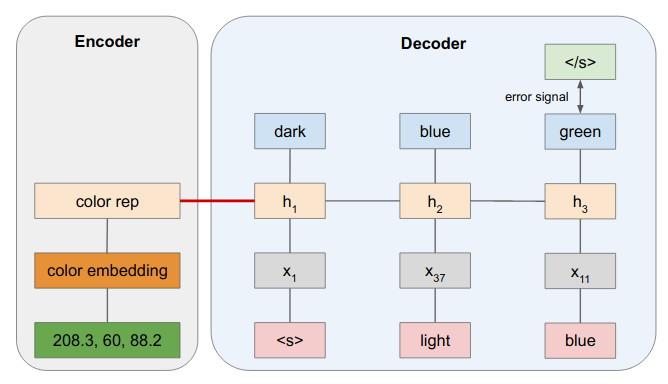

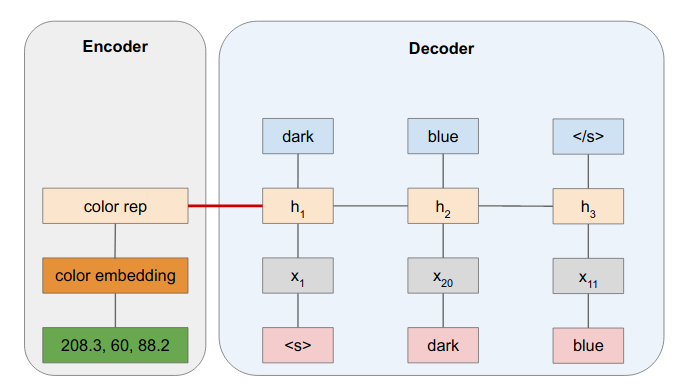

Example: Color Describer

Training with Teacher Forcing

Prediction

![]() Reference:

Reference:

- Blog: Language Grounding and Context

- CS224U Lecture Grounding, skip to 11th minute

- NLP: Entity Grounding

- CS 395T

- Grounded Language Learning: Where Robotics and NLP Meet IJCAI 2018

- CMU 10-808: Language Grounding to Vision and Control

- COMP 790.139 Processing: Grounded Language for Robotics

-

AAAI2013 Talk on Grounded Language Learning by Prof. Raymond J. Mooney from UT Austin

Evaluation

Classifier Comparison

Suppose you’ve assessed two classifier models. Their performance is probably different to some degree. What can be done to establish whether these models are different in any meaningful sense?

Confidence intervals

If you can afford to run the model multiple times, then reporting confidence intervals based on the resulting scores could suffice to build an argument about whether the models are meaningfully different.

The following will calculate a simple $95\%$ confidence interval for a vector of scores vals:

def get_ci(vals):

if len(set(vals)) == 1:

return (vals[0], vals[0])

loc = np.mean(vals)

scale = np.std(vals) / np.sqrt(len(vals))

return stats.t.interval(0.95, len(vals)-1, loc=loc, scale=scale)

It’s very likely that these confidence intervals will look very large relative to the variation that you actually observe. You probably can afford to do no more than $10–20$ runs. Even if your model is performing very predictably over these runs (which it will, assuming your method for creating the splits is sound), the above intervals will be large in this situation. This might justify bootstrapping the confidence intervals. I recommend scikits-bootstrap for this.

TL;DR: If model training time is short and you can run the model multiple times on the same train-test split, then create $n$ models and do the prediction of the test set on these $n$ models and for each test input you wil get $n$ predictions which will give you mean and variance and thus you can draw a confidence interval.

import scikits.bootstrap as boot

import numpy as np

boot.ci(np.random.rand(100), np.average)

Important: when evaluating multiple systems via repeated train/test splits or cross-validation, all the systems have to be run on the same splits. This is the only way to ensure that all the systems face the same challenges.

Learning curves with confidence intervals

- Incremental performance plots are the best augmented with confidence interval.

Example from paper Dingall and Potts 2018

The role of random parameter initialization

Most deep learning models have their parameters initialized randomly, perhaps according to some heuristics related to the number of parameters (Glorot and Bengio 2010) or their internal structure (Saxe et al. 2014). This is meaningful largely because of the non-convex optimization problems that these models define, but it can impact simpler models that have multiple optimal solutions that still differ at test time.

There is growing awareness that these random choices have serious consequences. For instance, Reimers and Gurevych (2017) report that different initializations for neural sequence models can lead to statistically significant results, and they show that a number of recent systems are indistinguishable in terms of raw performance once this source of variation is taken into account.

- For better or worse, the only response we have to this situation is to report scores for multiple complete runs of a model with different randomly chosen initializations.

- Confidence intervals and Statistical tests can be used to summarize the variation observed. If the evaluation regime already involves comparing the results of multiple train/test splits, then ensuring a new random initializing for each of those would seem sufficient.

Arguably, these observations are incompatible with evaluation regimes involving only a single train/test split, as in McNemar's test. However, as discussed above, we have to be realistic. If multiple run aren’t feasible, then a more heuristic argument will be needed to try to convince skeptics that the differences observed are larger than we would expect from just different random initializations.

- Strive to base your model comparisons in multiple runs on the same splits. This is especially important for deep learning, where a single model can perform in very different ways on the same data, depending on the vagaries of optimization.

For more evaluation refer to this cs224u notebook 2 ![]()

![]()

![]() Reference:

Reference: