Statistical Analysis (Part 1)

- What is P Value?

- Odds and log(Odds) and what is logits

- Understand the

logaxis - Different Statistical tests for feature selecton

- Difference between

Standard DeviationandStandard Error - Confidence interval (CI)

- Why bayesian inference can be difficult?

- How does Gibbs Sampling work?

- Importance Sampling and Monte Carlo

- Distribution

- Moments - Shape of You !!

- Central Limit Theorem

- Law of Large Number

- Maximum likelihood estimation

- Expectation Maximization (EM), Gaussian Mixture Model

- What is Calibration Plot?

- Monte carlo Gradient Estimate

What is P Value?

- for part 2 look here at notion/scribe-stat

In statistical hypothesis testing, the p-value decides whether to accept or reject null hypothesis.

- $p \lt$ threshold = Accept Alternate hypothesis (i.e reject null hypothesis)

- $p \gt$ threshold = Accept Null hypothesis

E.g: Say we measured the height of a woman is $147$ cm. Is the woman brazillian?

- Null hypothesis: The height of the woman comes from Woman height distribution from Brazil

- Alternate hypothesis: The height of the woman doesn’t come from Woman height distribution from Brazil

$p$-value is not probability value. Probability of getting 2 head in a row in coin tossing is different from $p$-value of getting 2 head in a row.

p-value = P(case1) + P(case2) + P(case3)

i.e p-value is sum of 3 probabilites

- case 1: Original event happen randomly

- case 2: Rare event similar to original event

- case 3: Rarest event

Some terms:

- Hypothesis Testing

- Normal Distribution

- What is P-value?

- Statistical Significance

Before we talk about what p-value means, let’s begin by understanding hypothesis testing where p-value is used to determine the statistical significance of our results.

-

Hypothesis testingis used to test the validity of a claim (null hypothesis) that is made about a population using sample data. The alternative hypothesis is the one you would believe if the null hypothesis is concluded to be untrue.

The lower the p-value, the more surprising the evidence is, the more ridiculous our null hypothesis looks.

If the p-value is lower than a predetermined significance level (people call it alpha, I call it the threshold of being ridiculous — don’t ask my why, I just find it easier for me to understand), then we reject the null hypothesis.

- In my opinion,

p-valuesare used as a tool to challenge our initial belief (null hypothesis) when the result is statistically significant. The moment we feel ridiculous with our own belief (provided the p-value shows the result is statistically significant), we discard our initial belief (reject the null hypothesis) and make a reasonable decision.

Statistical Significance

Finally, this is the final stage where we put everything together and test if the result is statistically significant.

Having just the p-value is not enough, we need to set a threshold (aka significance level — alpha). The alpha should always be set before an experiment to avoid bias. If the observed p-value is lower than alpha, then we conclude that the result is statistically significant.

The rule of thumb is to set alpha to be either 0.05 or 0.01 (again, the value depends on your problems at hand).

Reference:

What is p-values?

How it is decided for rejecting null hypothesis? Why it’s called null hypothesis?

-

Null hypothesismeans the hypothesis which you want to nullify. So there is analternate hypothesis, which will be accepted if the null hypothesis is rejected. - A

p-valueis the probability of finding some sample outcome or a more extreme one if the null hypothesis is true. -

Example: I want to know if happiness is related to wealth among Dutch people. One approach to find this out is to formulate a null hypothesis. Since “related to” is not precise, we choose the opposite statement as our null hypothesis:

The correlation between wealth and happiness is zero among all Dutch people.

- We’ll now try to refute this hypothesis in order to demonstrate that happiness and wealth are related all right.

- Now, we can’t reasonably ask all 17,142,066 Dutch people how happy they generally feel. So we’ll ask a sample (say, 100 people) about their wealth and their happiness. The correlation between happiness and wealth turns out to be 0.25 in our sample. Now we’ve one problem: sample outcomes tend to differ somewhat from population outcomes.

- How we can ever say anything about our population if we only have a tiny sample from it.

- So how does that work? Well, basically, some sample outcomes are highly unlikely given our null hypothesis.

- If our population correlation really is zero, then we can find a sample correlation of 0.25 in a sample of N = 100. The probability of this happening is only 0.012. So it’s very unlikely. A reasonable conclusion is that our population correlation wasn’t zero after all.

- Conclusion: we reject the null hypothesis. Given our sample outcome, we no longer believe that happiness and wealth are unrelated. However, we still can’t state this with certainty.

Reference:

Odds and log(Odds) and what is logits

Understand the log axis

Different Statistical tests for feature selecton

See here ![]()

Difference between Standard Deviation and Standard Error

- Check here too notion/scribe-stat

Standard Deviation of the

meansis called Standard Error

- SD quantifies the variation within a set of measurement

- SE quantifies the variation in the means from multiple set of measurements. It’s

SD of meansfrom multiple set of measurement of the same population. It has a simple formula which helps to find SE without repeating the measurement exercise. The formula is $\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}$.

Reference:

Confidence interval (CI)

Therer are many ways to calculate CI and bootstrapping is one of them.

The $95\%$ CI is just an interval that covers $95\%$ of the means.

Why bayesian inference can be difficult?

Determining the posterior distribution directly from the Byes’ rule involves computing the evidence i.e marginal likelihood. For continuous parameters, the integral can be impossible to solve analytically.

Historically the difficulty of the integration was bypassed by restricting the models to relatively simple likelihood functions with corresponding formulas for prior distribution - conjugate prior, that played nice with the likelihood functions to give us a tractable solution.

When the conjugate prior approach doesn’t work, another approach is the

- Approximate the original functions with other functions, which are easier to work with and then show that the approximate is reasonably good under typical conditions. This is known as

Variational Approximation.

Another kind of approximation involves,

- Randomly sampling large number of representative combinations of parameter values from the posterior distribution. These types of algorithms are known as

MCMCalgorithm. These methods help to calculate the posterior distribution without calculating the integral.

How does Gibbs Sampling work?

Gibbs Sampling is a MCMC method to draw samples from a potentially really really complicated, high dimensional distribution, where analytically, it’s hard to draw samples from it. The usual suspect would be those nasty integrals when computing the normalizing constant of the distribution, especially in Bayesian inference. Now Gibbs Sampler can draw samples from any distribution, provided

- You can provide all of the conditional distributions of the joint distribution analitically.

Reference:

Importance Sampling and Monte Carlo

Distribution

While the concept of probability gives us the mathematical calculations, distributions help us actually visualize what’s happening underneath.

Uniform Distribution

A variable X is said to be uniformly distributed if the density function is:

where $-\infty<a<=x<=b<\infty$

Bernoulli Distribution

Story: All you cricket junkies out there! At the beginning of any cricket match, how do you decide who is going to bat or ball? A toss! It all depends on whether you win or lose the toss, right? Let’s say if the toss results in a head, you win. Else, you lose. There’s no midway.

Formulation: A Bernoulli distribution has only two possible outcomes, namely 1 (success) and 0 (failure), and a single trial. So the random variable $X$ which has a Bernoulli distribution can take value 1 with the probability of success, say p, and the value 0 with the probability of failure, say q or 1-p.

The probability mass function is given by:

where $x \in (0, 1)$.

The expected value of a random variable X from a Bernoulli distribution is found as follows:

The variance of a random variable from a bernoulli distribution is:

Binomial Distribution

Story: Let’s get back to cricket. Suppose that you won the toss today and this indicates a successful event. You toss again but you lost this time. If you win a toss today, this does not necessitate that you will win the toss tomorrow. Let’s assign a random variable, say X, to the number of times you won the toss. What can be the possible value of X? It can be any number depending on the number of times you tossed a coin.

Formulation: An experiment with only two possible outcomes repeated n number of times is called binomial. The parameters of a binomial distribution are n and p where n is the total number of trials and p is the probability of success in each trial. If x is the total number fof success, we can write:

On the basis of the above explanation, the properties of a Binomial Distribution are:

- Each trial is independent.

- There are only two possible outcomes in a trial- either a success or a failure.

- A total number of n identical trials are conducted.

- The probability of success and failure is same for all trials. (Trials are identical.)

- Mean: $\mu = n*p$

- Variance:

Normal Distribution:

Normal distribution represents the behavior of most of the situations in the universe (That is why it’s called a “normal” distribution. I guess!).

The large sum of (small) random variables often turns out to be normally distributed, contributing to its widespread application ~ Central Limit Theorem

Any distribution is known as Normal distribution if it has the following characteristics:

- The mean, median and mode of the distribution coincide.

- The curve of the distribution is bell-shaped and symmetrical about the line $x=\mu$ .

- The total area under the curve is

1. - Exactly half of the values are to the left of the center and the other half to the right.

A normal distribution is highly different from Binomial Distribution. However, if the number of trials approaches infinity then the shapes will be quite similar.

The PDF of a random variable X following a normal distribution is given by:

where $-\infty<x<\infty$

A standard normal distribution looks as follows:

Poisson Distribution

- For more look here at notion/scribe-stat

Story: Suppose you work at a call center, approximately how many calls do you get in a day? It can be any number. Now, the entire number of calls at a call center in a day is modeled by Poisson distribution. Some more examples are

- The number of emergency calls recorded at a hospital in a day.

- The number of thefts reported in an area on a day.

- The number of customers arriving at a salon in an hour.

Poisson Distribution is applicable in situations where events occur at random points of time and space wherein our interest lies only in the number of occurrences of the event.

A distribution is called Poisson distribution when the following assumptions are valid:

- Any successful event should not influence the outcome of another successful event.

- The probability of success over a short interval must equal the probability of success over a longer interval.

- The probability of success in an interval approaches zero as the interval becomes smaller.

Formulation: Now, if any distribution validates the above assumptions then it is a Poisson distribution. Some notations used in Poisson distribution are:

- $\lambda$ is the rate at which an event occurs,

- $t$ is the length of a time interval,

- $X$ is the number of events in that time interval.

Here, $X$ is called a Poisson Random Variable and the probability distribution of $X$ is called Poisson distribution.

Let $\mu$ denote the mean number of events in an interval of length t. Then, $\mu = \lambda*t$.

The PMF of X following a Poisson distribution is given by:

where $x=0,1,2,3,…$

- Mean: $E(X) = \mu$

- Variance: $Var(X) = \mu$

Exponential Distribution

Story: Let’s consider the call center example one more time. What about the interval of time between the calls? Here, exponential distribution comes to our rescue. Exponential distribution models the interval of time between the calls.

Other examples are:

- Length of time between metro arrivals,

- Length of time between arrivals at a gas station

- The life of an Air Conditioner

Exponential distribution is widely used for survival analysis. From the expected life of a machine to the expected life of a human, exponential distribution successfully delivers the result.

Formulation: A random variable $X$ is said to have an exponential distribution with PDF:

where $x ≥ 0$ and parameter $\lambda>0$ which is also called the rate.

For survival analysis, $\gamma$ is called the failure rate of a device at any time t, given that it has survived up to t.

Mean and Variance of a random variable X following an exponential distribution:

- Mean: $E(X) = \frac{1}{\lambda}$

- Variance: $Var(X) = \frac{1}{\lambda^2}$

Gamma Distribution:

We now define the gamma distribution by providing its PDF: A continuous random variable $X$ is said to have a gamma distribution with parameters $\alpha>0$ and $\lambda>0$, shown as $X \sim Gamma(\alpha,\lambda)$, if its PDF is given by:

If we let $\alpha=1$, we obtain:

Thus, we conclude $Gamma(1,\lambda)=Exponential(\lambda)$. More generally, if you sum n independent $Exponential(\lambda)$ random variables, then you will get a $Gamma(n,\lambda)$ random variable.

How all the distributions are related?

Relation between Exponential and Poisson Distribution:

If the times between random events follow exponential distribution with rate $\lambda$, then the total number of events in a time period of length t follows the Poisson distribution with parameter $\lambda t$.

Moments - Shape of You !!

Moments try to measure the shape of the probability distribution function.

- The zeroth moment is the total probability of the distribution which is 1.

- The first moment is the mean.

- The second moment is the variance.

- The third moment is the skew which measures how lopsided the distribution is.

- The fourth moment is kurtosis which is the measure of how sharp is the peak of the graph.

Moments are important because, under some assumptions, moments are a good estimate of how the population probability distribution is based on the sample distribution. We can even have a good feel of how far off the population moments are from our sample moments under some realistic assumptions. And once the population moments are known that means the shape of the population probability distribution is known as well.

Reference:

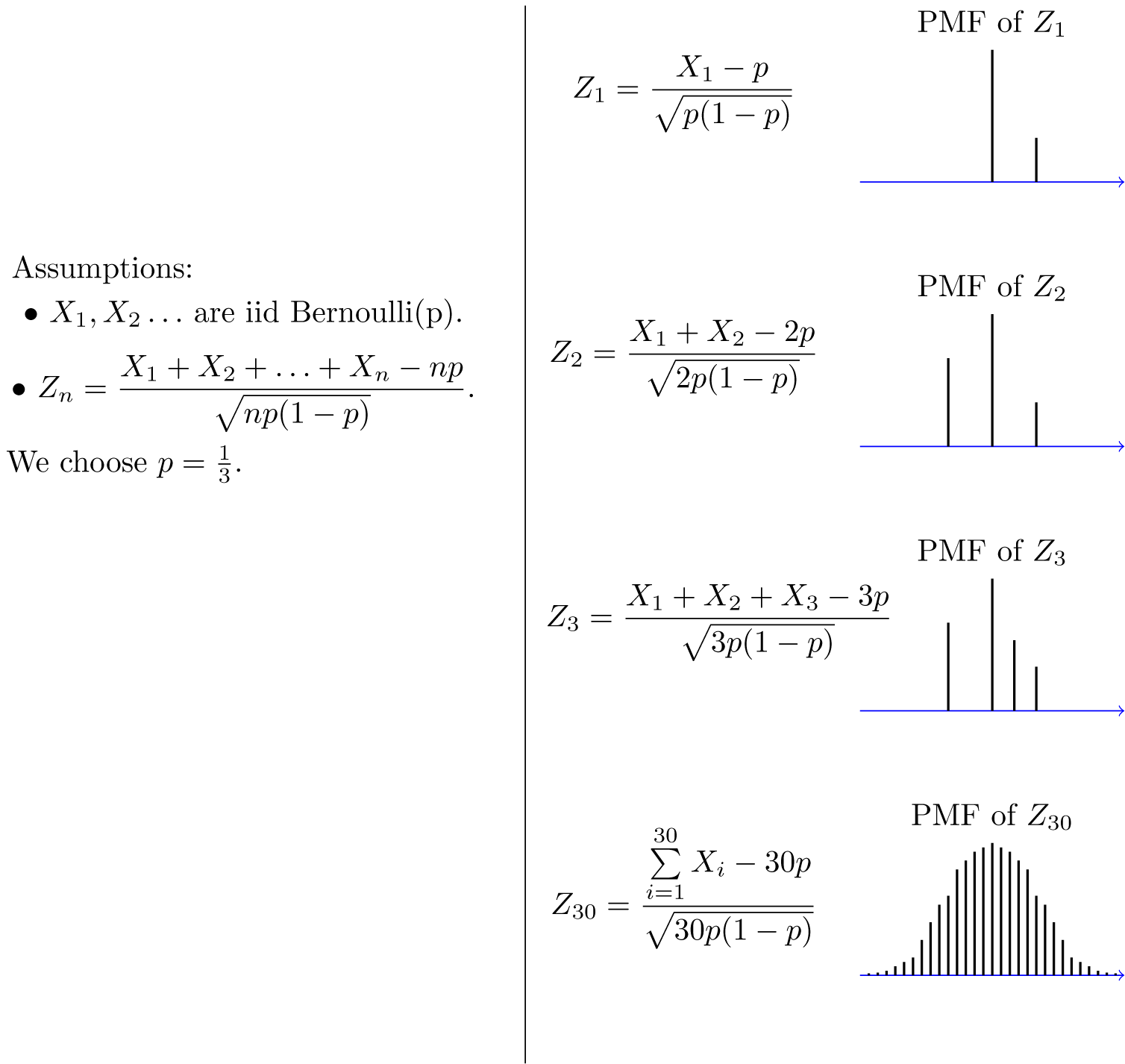

Central Limit Theorem

In probability theory, the central limit theorem (CLT) establishes that, in some situations, when independent random variables are added, their properly normalized sum tends toward a normal distribution (informally a “bell curve”) even if the original variables themselves are not normally distributed.

The theorem is a key concept in probability theory because it implies that probabilistic and statistical methods that work for normal distributions can be applicable to many problems involving other types of distributions. (wiki)

Formulation: Suppose that $[X_1, X_2 ,…,X_n]$ are i.i.d. random variables with expected values $E(X_{\large i})=\mu < \infty$ and variance $\mathrm{Var}(X_{\large i})=\sigma^2 < \infty$. Then as we saw above, the sample mean $\overline{X}={\large\frac{X_1+X_2+…+X_n}{n}}$ has mean $E(\overline{X})=\mu$ and variance $\mathrm{Var}(\overline{X})={\large \frac{\sigma^2}{n}}$. Thus the normalized random variable is:

which has mean $E(Z_n)=0$ and variance $Var(Z_n)=1$, i.e the random variable $Z_n$ converges in distribution to the standard normal random variable as n goes to infinity, i.e

where $\Phi(x)$ is the standard normal CDF.

Let’s say $X$ follows Binomial distribution. Then as ${n \rightarrow \infty}$, the distribution of $Z_n$ looks like this:

Reference:

Law of Large Number

The law of large numbers has a very central role in probability and statistics. It states that if you repeat an experiment independently a large number of times and average the result, what you obtain should be close to the expected value.

There are two main versions of the law of large numbers. They are called the weak and strong laws of the large numbers.

For i.i.d. random variables $X_1,X_2,…,X_n$, the sample mean, denoted by $\bar X$, is defined as: $\bar X = \frac{1}{n}\Sigma X_i$

Reference:

Variational Inference:

- Nips 2016 Tutorial

- Building Machines that Imagine and Reason Principles and Applications of Deep Generative Models Shak

Maximum likelihood estimation

Let’s assume $D$ is the data that comes from distribution parameterized by $\theta$. In MLE, given data we want to find the distribution (parameterized by $\theta$) from which the probability of geting the data is maximum.

Where

- $p(\theta \vert D)$ is the posterior probability of $\theta$ given $D$

- $p(D \vert \theta)$ is likelihood (i.e likelihood of data $D$ given $\theta$) and can be written as $\mathcal{L}(D \vert \theta)$ or $\mathcal{L}(D ; \theta)$.

- $p(\theta)$ is the prior

posterior $\propto$ likelihood $\times$ prior

Expectation Maximization (EM), Gaussian Mixture Model

Gaussian mixture models are a probabilistic model for representing normally distributed subpopulations within an overall population. Mixture models in general don’t require knowing which subpopulation a data point belongs to, allowing the model to learn the subpopulations automatically. Since subpopulation assignment is not known, this constitutes a form of unsupervised learning.

For example, in modeling human height data, height is typically modeled as a normal distribution for each gender with a mean of approximately 5’10” for males and 5’5” for females. Given only the height data and not the gender assignments for each data point, the distribution of all heights would follow the sum of two scaled (different variance) and shifted (different mean) normal distributions. A model making this assumption is an example of a Gaussian mixture model (GMM), though in general a GMM may have more than two components. Estimating the parameters of the individual normal distribution components is a canonical problem in modeling data with GMMs.

A Gaussian mixture model is parameterized by two types of values, the mixture component weights and the component means and variances/covariances. For a Gaussian mixture model with $K$ components, the $k^{\text{th}}$ component has a mean of $\mu_k$ and variance of $\sigma_k$ for the univariate case and a mean of $\vec{\mu}k$ and covariance matrix of $\vec{\sigma}_k$ for the multivariate case. The mixture component weights are defined as $\phi_k$ for component $C_k$, with the constraint that $\sum{i=1}^k \phi_i = 1$, so that the total probability distribution normalizes to $1$. If the component weights aren’t learned, they can be viewed as an a-priori distribution over components such that . If they are instead learned, they are the a-posteriori estimates of the component probabilities given the data.

One-dimensional Model:

Multi-dimensional Model

Learning the Model

If the number of components $K$ is known, expectation maximization is the technique most commonly used to estimate the mixture model’s parameters. In frequentist probability theory, models are typically learned by using maximum likelihood estimation techniques, which seek to maximize the probability, or likelihood, of the observed data given the model parameters. Unfortunately, finding the maximum likelihood solution for mixture models by differentiating the log likelihood and solving for 0 is usually analytically impossible.

Expectation maximization (EM) is a numerical technique for maximum likelihood estimation, and is usually used when closed form expressions for updating the model parameters can be calculated (which will be shown below). Expectation maximization is an iterative algorithm and has the convenient property that the maximum likelihood of the data strictly increases with each subsequent iteration, meaning it is guaranteed to approach a local maximum or saddle point.

Note: Read section 8.5.1 from book Element of Statistical Learning for an easy understanding.

Two Component Mixture Model:

Say we have $\mid Y \mid$ number of data-_points coming from 2 normal distribution, i.e. mixture of 2 gaussian distribution. Where $Y_1 \sim N(\mu_1, \sigma_1)$ and $Y_2 \sim N(\mu_2, \sigma_2)$ and $\mid Y \mid = \mid Y_1 \mid + \mid Y_2 \mid$. Our task is to figure out those 2 distribution. More formally we want to estimate $\hat\mu_1, \hat\sigma_1$ and $\hat\mu_2, \hat\sigma_2$. We want to model $Y$ as follows

where $\Delta \in {0,1}$ with $P(\Delta=1)=\pi$.

For simplicity we can think that $\mid Y \mid$ number of blue and yellow balls are there, where number of blue balls $\mid Y_1 \mid$ and number of yellow balls $Y_2$. Blue balls come from 1 normal distribution and yellow balls come from another normal distribution. Now given a ball we need to figure out whether the balls come from 1st Normal distribution (blue) or 2nd normal distribution. We can easily solve this using

K-Meansclustering. But K-Means is aHard-Clusteringproblem. Where assignment probability is 0 or 1. But Mixture model is aSoft Clusteringproblem and an iterative process and the assignment probability is $\in [0,1]$.

In the above notation we can think of $\pi$ as the mixing coefficient. We can think it as a prior probability.

Let $\phi_\theta(x)$ denotes the normal density with parameters $\theta = (\mu, \sigma^2)$. Then the density of $Y$ is

Now we wish to fit this model to data by maximum likelihood estimation. The parameters are $\theta = (\pi, \theta^1, \theta^2) = (\pi, \mu_1, \sigma_1^2, \mu_2, \sigma_2^2)$.

The log likelihood based on all the training case is:

But direct maximization (by taking grad and set to 0) is difficult due to the sum inside log.

So we apply Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm.

- s1: guess: $\pi, \theta_1, \theta_2$

- s2: While $(oldLogLikelihood - Likelihood) > tolerance$

- s3: Expectaton Step: Find Posterior Probability (

Responsibility)

- s3: Expectaton Step: Find Posterior Probability (

- Where $p(\theta_2) = \pi$, $p(\theta_1) = 1-\pi$

- $p(y_i) = p(y_i \vert \theta_1)p(\theta_1) + p(y_i \vert\theta_2)p(\theta_2)$

-

$p(y_i \vert \theta_2) = N(\mu_2, \sigma_2)$ [use from s1 (1st time) and s4 (later)]

- s4: Maximization Step: compute the weighted mean and variances

- s5: calculate loglikelihood:

So we are trying to maximize the log-likelihood through this iterative approach. The above algorithm is a simple version for 1D data. If the data is 2D then instead of variance $\sigma^2$, we will have covariance matrix $\Sigma$ because of Multivariate Gaussian. But the basic procedure is like this.

For more details, read the following references.

-

YouTube,

[Elements of Statistical Learning, section

8.5.1] - code_implementation

- EM_algo_python_code

- code_other

- [book_Simon_Prince_ch7]

- imp_source_1

- imp_source_2

What is Calibration Plot?

When I build a machine learning model for classification problems, one of the questions that I ask myself is why is my model not crap? Sometimes I feel that developing a model is like holding a grenade, and calibration is one of my safety pins.

Evaluating probabilistic predictions

In machine learning, most classification models produce predictions of class probabilities between 0 and 1, then have an option of turning probabilistic outputs to class predictions.

A model’s output can be viewed as a statement saying how likely something should happen.

- A probabilistic model is calibrated if I binned the test samples based on their predicted probabilities, each bin’s true outcomes has a proportion close to the probabilities in the bin.

Predicted probabilities that match the expected distribution of probabilities for each class are referred to as calibrated.

Calibration of Predictions

There are two concerns in calibrating probabilities; they are

- Diagnosing the calibration of predicted probabilities

- The calibration process itself.

Reliability Diagrams (Calibration Curves)

A reliability diagram is a line plot of the relative frequency of what was observed (y-axis) versus the predicted probability frequency (x-axis).

They consist of a plot of the observed relative frequency against the predicted probability

Method:

- Specifically, the predicted probabilities are divided up into a fixed number of buckets ($n$ bins) along the x-axis.

- For each bin, find the average probability of

class=1this gives youx. - The number of ground truths, where

class=1are then counted for each bin (e.g. the relative observed frequency), divided by the total events in that bin. This givesyfor that bin. - Thus for each bin, you get $(x,y)$ and then you plot them.

- If there are $n$ bins, then there will be $n$ points on the calibration curve.

These plots are commonly referred to as reliability diagrams in forecast literature, although may also be called calibration plots or curves as they summarize how well the forecast probabilities are calibrated.

Interpretation:

The better calibrated or more reliable a forecast, the closer the points will appear along the main diagonal from the bottom left to the top right of the plot.

- Below the diagonal: The model has over-forecast; the predicted probabilities are too large.

- Above the diagonal: The model has under-forecast; the probabilities are too small.

How predictions are calibrated?

The predictions made by a predictive model can be calibrated. Calibrated predictions may (or may not) result in an improved calibration plot on a reliability diagram.

Some algorithms are fit in such a way that their predicted probabilities are already calibrated. Without going into details why, logistic regression is one such example.

Other algorithms do not directly produce predictions of probabilities, and instead a prediction of probabilities must be approximated. Some examples include neural networks, support vector machines, and decision trees. The predicted probabilities from these methods will likely be uncalibrated and may benefit from being modified via calibration.

Calibration of prediction probabilities is a rescaling operation that is applied after the predictions have been made by a predictive model.

There are two popular approaches to calibrating probabilities:

- Platt Scaling

- Platt Scaling is simpler and is suitable for reliability diagrams with the S-shape.

- Isotonic Regression

- Isotonic Regression is more complex, requires a lot more data (otherwise it may overfit), but can support reliability diagrams with different shapes (is nonparametric).

Implementation

# SVM reliability diagram with calibration

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.calibration import CalibratedClassifierCV

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.calibration import calibration_curve

from matplotlib import pyplot

# generate 2 class dataset

X, y = make_classification(n_samples=1000, n_classes=2, weights=[1,1], random_state=1)

# split into train/test sets

trainX, testX, trainy, testy = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.5, random_state=2)

# fit a model

model = SVC()

calibrated = CalibratedClassifierCV(model, method='sigmoid', cv=5)

calibrated.fit(trainX, trainy)

# predict probabilities

probs = calibrated.predict_proba(testX)[:, 1]

# reliability diagram

fop, mpv = calibration_curve(testy, probs, n_bins=10, normalize=True)

# plot perfectly calibrated

pyplot.plot([0, 1], [0, 1], linestyle='--')

# plot calibrated reliability

pyplot.plot(mpv, fop, marker='.')

pyplot.show()

Blue line: Uncalibrated, Orange line: calibrated. After calibration, the orange line is hugging the diagonal line more closely

-

sklearn.calibration.calibration_curve()for getting the values for plotting incalibration curve -

sklearn.calibration.CalibratedClassifierCV()is used for calibrating the probabilities.- Probability calibration with isotonic regression or sigmoid.

- With this class, the

base_estimatoris fit on the train set of the cross-validation generator and the test set is used for calibration. The probabilities for each of the folds are then averaged for prediction.

Reference:

Monte carlo Gradient Estimate

Comprehensive Survey